Fecha de recepción: 1 de julio 2017

Fecha de aceptación: 31 de julio 2017

Chinese Aid to Latin America and the Caribbean:

Evolution and Prospects

Ayuda al desarrollo de China a América Latina y el Caribe:

Evolución y perspectivas a futuro

Artículo Resultado de Investigación

*Candidato doctoral en Ciencia Política de la Universidad de los Andes y Magister en Cooperación internacional para el desarrollo. Docente del master en Cooperación y Desarrollo de la Universidad San Buenaventura, egresado de la Universidad de Belén (Palestina) y Roma Tre (Italia).

Abstract

In the last decade, China has risen as a very visible player in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), through its foreign aid, its investments and its bilateral trade. While extensive research has been conducted on Chinese aid to Africa, this paper will focus instead on the Chinese aid to LAC. After an overview of the historical evolution of Chinese aid to the region, and an attempt to quantify the amount of Chinese aid received by LAC as compared to other developing regions, this paper considers the three main motives which may drive China to provide aid, such as the needs of the recipient, the institutional characteristics of the beneficiary, and the political and economic interests of the donor country. The article concludes with an appraisal of the potential benefits and negative impacts of the Sino-LAC relationship, finding among potential concerns the unconditionality of Chinese foreign aid and its unbalanced trade relationship with the region.

Keywords: China’s Foreign Aid, Emerging Donors, Aid Allocation, Latin American and the Caribbean.

Resumen

En la última década, China se ha posicionado como un actor muy visible en América Latina y el Caribe (ALC), a través de su ayuda externa, sus inversiones y su comercio bilateral. Aunque existe una amplia literatura e investigación sobre los efectos de la ayuda china a África, este documento se centrará en la ayuda china a ALC. Después de una visión general de la evolución histórica de la ayuda china a la región y un intento de cuantificar la cantidad de ayuda china recibida por ALC en comparación con otras regiones en desarrollo, este trabajo considera que son tres los motivos principales que pueden conducir a China a proporcionar ayuda, tales como la necesidad del receptor, las características institucionales del beneficiario y los intereses políticos y económicos del país donante. El artículo concluye con una evaluación de los beneficios potenciales y los impactos negativos de la relación sino-latinoamericana, encontrando entre posibles preocupaciones la incondicionalidad de la ayuda externa china y su desequilibrada relación comercial con la región.

Palabras clave: Ayuda Oficial de China, Donantes emergentes, Asignación de la ayuda, America Latina y el Caribe.

Introduction

In the last decades China has been able to increase its influence on global affairs and development, due to its rapid expansion of GDP and trade volumes, through several channels which include its foreign aid and strategic trade relationships, which in turn are used as a tool to further its strategic interests in developing regions such as Africa, South Asia and Latin America. While substantial research has been conducted in relation to Chinese aid to Africa, its aid to Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) has been given scarce consideration, despite the potential influence of Chinese financial flows over the region. In fact, upon entering the new century, the assistance provided to Latin America has sharply raised, both in terms of the number of recipient countries and in amount. From 2005 to 2012, China has provided to Latin American countries more than $87 billion USD in loans. In 2010, China’s loan commitments to Latin America of $37 billion USD were more for that year than the combined World Bank’s, Inter-American Development Bank’s and the United States Export-Import Bank’s loans (Gallagher et al., 2012). Actually, China pledged to direct a quarter trillion dollars (250 billions) to the region during the next decade (2015-2025) (Watson, 2015).

This article has the objective to analyze the evolution and prospects of Chinese foreign aid to LAC. In the first section, it presents an overview of its historical evolution, dividing the history of aid provision by China in six phases, each of which responds to different strategic imperatives. The second section will take into account the different quantitative measures and estimates of Chinese aid, as well as the type of projects implemented, including an attempt to quantify the amount of aid received by LAC as compared to other developing regions. The third section delves into the different motivations and strategic interests of the Sino-Latin America aid and trade relations, focusing on three main groups of motives for providing aid: the need of the recipient, the institutional characteristics of the beneficiary, and the political and economic interests of the donor country. The fourth section provides an overview of the potential benefits, as well as the negative effects, of Chinese unconditional foreign aid and of its unbalanced trade relationship with the region.

I. Six phases of Chinese aid to Latin America and the Caribbean

After the Chinese Communist Party took control of mainland China, after the defeat and resettlement of the Nationalist Party to Taiwan, the People’s Republic of China started delivering foreign aid to developing nations in 1950, by providing aid assistance to North Korea. Following the 1956 Bandung Asian-African Conference, China extended its aid (consisting of donations and interest-free loans) to non-Communist countries, such as Cambodia, Egypt and Nepal (Bartke, 1989). Since then, six phases in China’s aid delivery can be identified. I summarize them below.

i) The first phase of Chinese aid (1956-1969) had been primarily motivated by political/ideological considerations. Indeed, China backed the independence movements of African countries, and had used foreign aid to sustain the struggle versus colonial powers (Davies, 2007). On the other hand, the founding principles of Chinese aid provision emphasized the self-sufficiency of recipient nations, as well as mutual benefit (Bartke, 1989; Dreher & Fuchs, 2012); such doctrine was formalized in 1964 in the “Eight Principles for Economic Aid and Technical Assistance to Other Countries” (State Council, 2011). Latin American countries were reluctant to establish diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China in Beijing, recognizing instead the Republic of China in Taiwan as the legitimate government of the Chinese people (Hearn & León-Manríquez, 2011, p.6). Between the 1950s and 1970s, in fact, Latin American governments were steadily anti-communist and pro-Washington, with the only exception of Cuba; as such, Cuba was the only Latin American nation to establish formal diplomatic relations with China and to receive its assistance. From 1959 (when Castro took power in Cuba) to 1965, both countries signed two five-year agreements and several annual trade agreements under which China pledged to support Cuba through preferential trade policies, interest-free loans and material assistance, among others (State Council, 2011).

ii) The 9th Congress of Chinese Communist Party, held in 1969, is understood to be the beginning of the second phase (1970-1978) of Chinese aid; since then, the quantity of aid provided increased, in agreement with Chairman Mao Zedong’s strategy of assuming political guidance of the Third World. Such strategy included the promotion and formation “of Maoist factions in the Communist parties of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Peru, and others” (Hearn & León-Manríquez, 2011, p.8). Chinese attempts to spread communist revolutions in the region declined in the late 1970s, when negotiations with Nixon’s presidency in the United States led China to seek more friendly diplomatic ties with developing countries (Hearn & León-Manríquez, 2011, p.9). In accordance with the claim of increased international recognition, in 1971 China substituted Taiwan in the UN Security Council; supposedly, the flows of aid to the African countries guaranteed the necessary support to obtain this position (Davies, 2007). Following the demise of Communist Party Vice-President Lin Biao in 1973, nevertheless, foreign aid was compressed under the leadership of Premier Zhou Enlai (Bartke, 1989; Dreher & Fuchs, 2012). However, the 1970s were marked by an increase in the number of countries that established diplomatic relations with China, as did the recipients of Chinese aid in the LAC region, including Chile, Peru, Guyana, Jamaica, and others. According to treaties signed between China and these countries, the Asian country offered loans without interest for cooperation in sectors such as agriculture and textiles. In addition, the Chinese Red Cross provided financial assistance on numerous occasions to Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala in Central America to alleviate the aftermath of natural disasters (State Council, 2011).

iii) The third phase (1979-89) of Chinese aid began after the deaths of Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai in 1976, when Deng Xiaoping assumed the direction of the Communist Party of China in 1978. The new leader implemented more pragmatic decisions about its foreign policy (including revised aid policies) and China opened its doors to the West. The economic reform package (called “reform and opening up”) began to introduce market principles, as well as gradually granting access to the Chinese economy to foreign capital investment and international trade. Economic concerns started to be more significant for decisions on foreign aid budget allocation, and China started to form stronger relationships with developing regions. Assistance to Latin America was characterized by numerous small-scale individual projects, and “mutually advantageous” programs were promoted (OECD, 1987). China began to foster South-South cooperation, as well as economic and technological cooperation, both guided by the principles of equality, mutual benefit, effectiveness, diversification and common development (State Council, 2011). Although Chinese aid had initially offered aid in the form of subsidies or long-term credits without interest, the conditions in the 1980s became stricter yet still advantageous for Latin American countries, which in turn started their own process of opening their economies to the global market. It was during this decade that China gave a new focus to its foreign aid, emphasizing the improvement and maintaining of existing programs (Bartke, 1989; Dreher & Fuchs, 2012).

iv) The fourth phase (1990-1995) began following the Tiananmen Square episode in 1989, when China energetically pursued diplomatic support and considerably boosted its foreign aid. In particular, aid to African nations increased (Taylor, 1998; Brautigam, 2008, 2010; Dreher & Fuchs, 2012). In Africa, indeed, responses to the slaughter were substantially milder compared to reactions from the West, to the extent that some African countries were even supportive of the actions undertaken (Taylor, 1998). As Taylor puts it (1998, p.450), such aid policies were a “quick and comparatively cheap way by which Beijing could reward those countries that had stood by China” during the crisis, in addition to strengthening relationships. On the other hand, in the late 1980s China strengthened its “checkbook diplomacy”, as a reaction to Taiwan’s transition to democracy, which led to an increased recognition to the ROC; in fact, seven countries (Belize, Guinea-Bissau, Nicaragua, Bahamas, Grenada, Liberia, and Lesotho) switched back their diplomatic recognition to Taiwan. Such a rivalry produced sort of a “bidding war” in which offers of aid by both sides escalated (Brautigam, 2010, p.11; Rich, 2009). Additionally, after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1990, Chinese international relations became less ideological (Hearn & León-Manríquez, 2011, p.12). The literature stresses the importance of economic considerations, which have increasingly become China’s predominant aid strategy (Davies, 2007; Pehnelt, 2007). In fact, Chinese planners were conscious that the scarcity of resources, mainly in domestic energy, could rapidly hinder domestic production; to counter that, they operated “to position the country to overcome that challenge” (Brautigam, 2008, p.11). Specifically, foreign aid restructurings of 1995 headed towards market-oriented attitudes and highlighted the connection between aid, commerce and investment (Brautigam, 2009; Dreher & Fuchs, 2012).

v) Following this market-oriented reform, China’s aid activities entered an entirely different period compared to earlier stages (Kobayashi, 2008, p.7; Dreher & Fuchs, 2012), thus constituting the beginning for the fifth phase (1996-2005). The central objective of the reorganization was to increase the modes of delivery of foreign financing to developing nations. Apart of donations and interest-free credits (flexible and rapid financing forms), China also conceded preferential loans with subsidized interest, together with joint ventures and participation in comprehensive international cooperation projects and programs. China announced a twofold increase in its aid effort to Africa in order to “achieve the goal of mutual benefit and win-win between China and African countries» (Ministry of Commerce, ٢٠٠٧, p.٤١٦). At the turn of the new century, China underwent enormous development and became one of the most important economies in the world; it also increased the assistance it provides to Latin America, both in the number of receiving countries and in the amount disbursed. In 2004, the Forum for Economic and Trade Cooperation between China and the region is established.

vi) The most recent era for China’s aid program allegedly began in 2006, with China announcing a “new strategic partnership” in the context of the Forum of China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), when President Hu Jintao proclaimed the creation of the China-Africa Development Fund to advance Chinese investment in Africa with US$1 billion, expected to grow to US$5 billion, as well as announcing to double its aid effort to Africa from 2006 to 2009, with the aim of achieving the goal of mutual benefit and win-win between the PRC and African nations (Ministry of Commerce, 2009, p.416).

The growing importance of the links between China and Latin America and the Caribbean can be identified in five milestones during the most recent phase (2006-2016) (CEPAL, 2015, p.6). The first one is the publication in 2008 of the White Book on foreign relations between China and the region, a policy paper in which China exhibited at various points the orientation of their aid policies and development of bilateral relations, and explained its preliminary plans. A second milestone is the 2012 proposition by Premier Wen Jiabao, during a visit to the ECLAC (UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean), to strengthen political, economic and cooperation relations between China and LAC. A third turning point is the ambitious cooperation framework for 2015-2019, generally known as “1+3+6”, which was proposed in 2014 in Brazil at the first Summit of Leaders of China and LAC by President Xi Jinping. In this plan, “1” stands for “one plan”, referring to the 2015-2019 comprehensive plan, aimed at achieving inclusive growth and sustainable development; “3” stands for “three engines”, indicating the promotion of cooperation through trade, investment and financial co-operation; “6”, finally, stands for “six fields”, which refer to fostering industry connection in six co-operation priorities (energy and resources, infrastructure construction, agriculture, manufacturing, scientific and technological innovation, and information technologies). The fourth milestone is the joint adoption of the Cooperation Plan 2015-2019, at the First Ministerial Meeting of the CELAC-China Forum, held in Beijing in 2015. This document is a broad plan which considers thirteen thematic areas of work, eight of which are concentrated in economic areas. However, for the moment, this plan only indicates general objectives and broad lines of action, that have to be assumed to serve as a guideline for specific initiatives and projects, which supposes a strong challenge for politician and technicians, in order to allow the deepening of the relation and dialogue between CELAC and China; for the time being, the Asian country established a secretariat in order to monitor progress in such areas. The fifth and most recent breakthrough is the nine-day grand tour of official visits by Prime Minister Li Keqiang to Latin America (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru and, finally, to ECLAC headquarters in Santiago) in 2015, where he made clear that, despite decelerating growth on both sides of the Pacific, China will be contributing much more to the region in the forthcoming years, allocating many more billions and promising the construction of a trans-Amazon railway connecting Peru and Brazil, to enable China to cheaply import Brazilian iron and soy (CEPAL, 2015).

Regarding specifically the Caribbean nations, at the II Forum on Economic and Trade Cooperation between China and Caribbean held in 2007, China defined its proposal on the assistance it would provide in the following three years to the countries of the region with whom it maintains friendly relations. This proposal included granting preferential loans worth 4,000 million yuan (more than 526 million 2007 USD), conducting training programs for 2,000 people and sending agricultural experts, Chinese language teachers and medical teams to the region. After that, China has been actively executing the aid measures to Caribbean nations revealed at the III China-Caribbean Economic and Trade Cooperation Forum held in 2011. By the end of 2012, under such framework, China had delivered concessional loans (totaling 3 billion yuan, 450 million USD) to the Caribbean countries, primarily for the construction of infrastructure projects. Meanwhile, China trained over 500 officials and technical staff for the Caribbean countries, and held training courses for these countries, to establish earthquake and tsunami early warning and monitoring systems. China also built schools in Antigua & Barbuda and Dominica, sent medical teams and trained local medical staff in Dominica, and completed technical cooperation projects in agriculture and fishery in Dominica, Grenada and Cuba (State Council, 2014).

II. Amount and type of Chinese aid to Latin America and the Caribbean

Quantifying Chinese aid - When conducting empirical research on Chinese aid budget allocation, the main operative problem is that the Chinese government declines to publish full information on its annual bilateral aid allocations. Hence, estimations of the total size of China’s aid flows vary considerably. Part of the variation is stemming from the different delimitations of which flows are considered as development aid and which are not. Estimates show that Chinese aid has rapidly increased during the past decade. The United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID), estimates aid for Africa amounting to US$1.3-1.4 in 2006; professor Qi (2007) estimates that aid for Africa in 2007 was worth US$1.05 billion, being US$1.38 China’s total aid budget for that year. Between 2000 and 2013, Chinese development finance datasets show 2,312 projects in 50 countries, totaling $94.31 billion. According to the Financial Times’ estimates, China outperformed the World Bank as the world’s largest provider of overseas loans to developing countries through its China Development Bank and China Export-Import Bank, amounting to at least US$110 billion in 2009 and 2010.

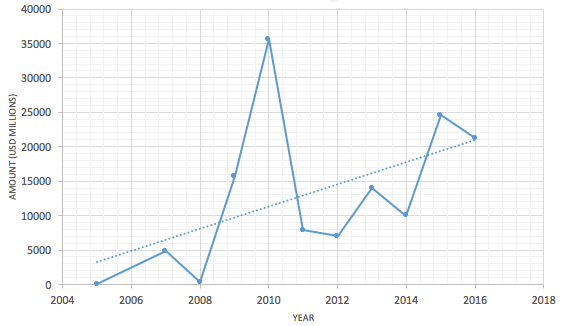

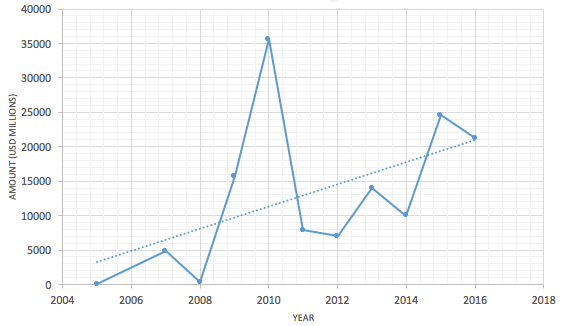

According to the Inter-American Dialogue database, during the sixth phase (2006-2016) China gave growing amounts of loans to the region (see Fig.1 below) covering different areas (in particular infrastructure, energy, and mining).

Fig.1 - Total amount of loans from China to Latin America and the Caribbean (2005-2016)

Source: Compiled by the author based on data from Gallagher & Myers (2016)

Venezuela is by far the country that has received the most loans from the PRC in the region, with 17 loans totaling $62,2 billion. Brazil was second, with ten loans totaling $36.8 billion, followed by Argentina (8 loans, $15.3 billion), Ecuador (13 loans, $17.4 billion), and Bolivia (10 loans, $3.5 billion) (Gallagher & Myers, 2016). Figures for the period 2006-2016 are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1 - Loans provided by China to countries of Latin America and the Caribbean in the sixth phase of Chinese aid (2006-2016)

|

Country

|

Number of Loans

|

Amount (USD millions)

|

|

Venezuela

|

17

|

62,200

|

|

Brazil

|

10

|

36,800

|

|

Ecuador

|

13

|

17,400

|

|

Argentina

|

8

|

15,300

|

|

Bolivia

|

10

|

3,500

|

|

Trinidad & Tobago

|

2

|

2,600

|

|

Jamaica

|

10

|

1,800

|

|

Mexico

|

1

|

1,000

|

|

Costa Rica

|

1

|

395

|

|

Barbados

|

1

|

170

|

|

Guyana

|

1

|

130

|

|

Bahamas

|

2

|

99

|

|

Peru

|

1

|

50

|

Source: Compiled by the author based on data from Gallagher & Myers (2016)

With the intention of silencing objections that China does not provide sufficient information on its aid program, the Chinese government published two White Papers on China’s Foreign Aid in 2011 and 2014 (State Council, 2011, 2014; Dreher & Fuchs, 2012). According to these official documents, China has provided aid to 161 countries until 2009, of which 123 developing countries received aid on a regular basis. This corresponds to 256.29 billion yuan ($38.54 billion USD), of which 41.4% were provided as grants, 29.9% as interest-free loans, and 28.7% in the form of concessional loans (State Council, 2011). From 2010 to 2012, China provided assistance to 121 countries: 30 in Asia, 51 in Africa, 9 in Oceania, 19 in Latin America and the Caribbean and 12 in Europe. China allocated a total of 89.34 billion yuan (14.41 billion U.S. dollars) for foreign assistance. Grants were 36.2 percent of the total assistance volume (32.32 billion yuan, 4.8 billion USD), interest-free loans were 8.1 percent of its foreign assistance volume (7.26 billion yuan, approximately 1 billion USD), concessional loans amounted to 55.7 percent of the total (49.76 billion yuan, 7 billion USD) in the same period (State Council, 2014). Still, it is not clear which financial flows are included in these calculations. Missing information on the degree of concessionality of Chinese loans makes it difficult to apply the definition of official development assistance (ODA) from the DAC. For this reason, few econometric studies have verified the causal mechanisms behind Chinese aid with hard data, and speculative claims about foreign aid from China remain mostly unchallenged.

AidData (Hawkins, 2010) provides project-level data for non-OECD suppliers of international development finance, such as China, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, which do not publish their own project-level data. In particular, they have tracked Chinese development finance to African countries for 2000 thru 2012, and used these methods to create a detailed project-level database of official Chinese development finance flows to Africa from 2000 to 2012. This database includes more than 1,950 pledged, initiated, and completed projects, worth over $84 billion USD. Dreher & Fuchs (2012) make use of AidData and various other datasets covering 1956-2006, to empirically test to which extent political and commercial interests shape China’s global aid allocation decisions. They estimate the determinants of China’s allocation of project aid, food aid, medical staff and total aid money to all developing countries, comparing its allocation decisions with traditional and other so-called emerging donors; these authors conclude that political considerations are an important determinant of global China’s allocation of aid and that it remains independent of democracy and governance in recipient countries. They also find no evidence that China’s aid allocation is dominated by natural resource endowments.

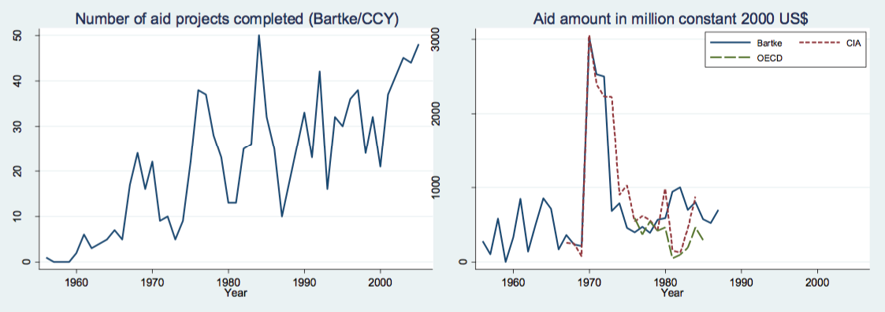

Another difficulty in doing econometric analysis of foreign aid is that global aid suffers great volatility: amounts of aid allocated each year, in general, vary substantially. Chinese aid is no exception, as shown by Figure 1, presenting a wide volatility in both the number of project completed and aid amounts.

Figure 2 – Volatility of Chinese aid across time (number of projects completed, and amount of aid in millions constant 2000 USD)

Source: Dreher and Fuchs (2012)

When conducting econometric research about foreign aid budget allocation, Gupta et al. (2006) recommend grouping foreign aid budget allocation and projects by phases, and not by single year, due to aid volatility. Following this suggestion, I estimate the relative importance of each region of the developing world for China foreign aid budget allocation in the six phases described in the first section, using datasets from Dreher and Fuchs (2012) and AidData (Hawkins, 2010). Conducting this exercise allows to visually represent the relative importance of Latin America and the Caribbean across time, as compared to other developing regions.

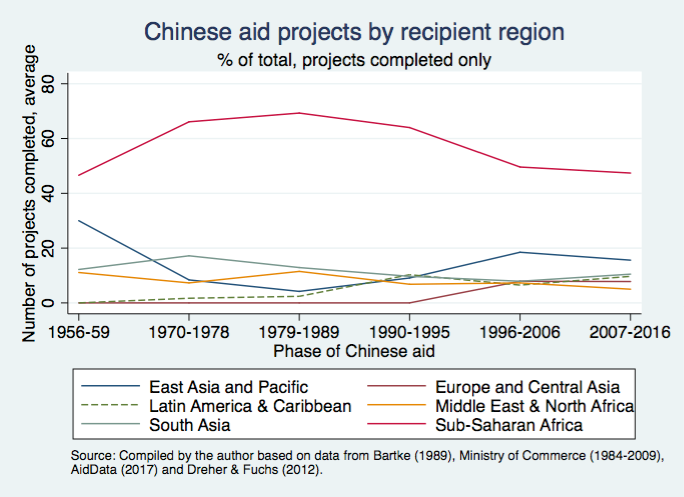

Figure 3 – Chinese aid to different developing regions (number of completed projects as % of total)

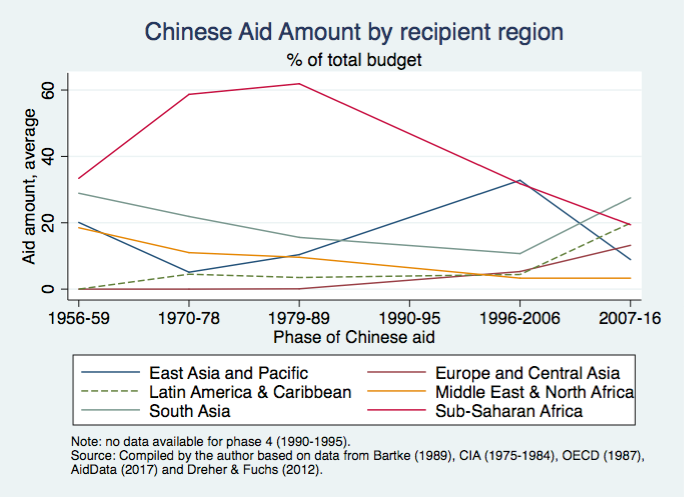

As illustrated in Figure 3, Sub-Saharan Africa is constantly the greatest recipient of Chinese project aid, accounting for more than 40% of projects throughout all phases. East Asia and Pacific, important due to geographical proximity, is the second region most benefitted, in the first, fifth and sixth phases. Latin America and the Caribbean received less aid than both the Middle East and North Africa and South Asia in the first three phases, until the fall of Soviet Union. It is only after 1990 that China increased the relative number of projects in the LAC region, which is in line with those regions in the fourth, fifth and sixth phases, obtaining around 10% of total Chinese aid projects. Coming to the amounts of aid, as shown by Figure 4 below, we can see that the share of Chinese aid allocated to Latin America and Caribbean has passed from less than 5% to 20% of its total budget, and it is now comparable with the amount of aid received by Sub-Saharan Africa. These combined figures show that Chinese aid has a special focus on Sub-Saharan Africa, especially regarding the number of projects; nevertheless, it maintains a global outlook, providing substantial levels of aid to all developing regions. Looking at LAC in particular, we can appreciate that while the share of aid projects remained substantially constant, the amount of aid provided has sharply increased in the last decade, reflecting the fact that greater attention is dedicated to the region, and bigger financial flows are dedicated by China to LAC, both in absolute terms and relative to the rest of the world.

Figure 4 – Chinese aid to different developing regions (number of completed projects as % of total)

Types of aid - Beginning in the 1990s, the reform of methods for providing aid to the outside world was deepened, diversifying and making them more flexible. The types of aid provided by China to the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean can be divided into six types: (i) humanitarian assistance, (ii) free material assistance, (iii) preferential loans, (iv) infrastructure construction, (v) vocational training programs and (vi) support to local organizations. They are summarized below:

i) First, humanitarian assistance was rapidly developed in emergency situations. China provided timely assistance, both financially and through donations/shipments of medical equipment, among others. Between 2003 and 2010, according to Chinese State Council, China has provided this type of assistance on more than 30 occasions to countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, including Cuba, Costa Rica, Mexico, Peru, Chile and Haiti. Of these, and despite having not yet established formal diplomatic relations with China, Haiti was conceded 93 million yuan (approximately 13.7 million 2010 USD) after the devastating earthquake of 2010 (State Council, 2011). In 2012, China helped Cuba to relief the consequences of hurricane Sandy, providing 100 tons of humanitarian aid (State Council, 2014)

ii) There has also been a significant increase in free material assistance. According to official data, in the 1990s, China made over 30 donations of industrial supplies, such as bicycles, agricultural and/or medical equipment, among others; between 2000 and 2008, this type of aid has multiplied, registering almost 50 donations, including telecommunications equipment, office supplies, cultural and sporting goods, and others, with an increasingly high technological content (State Council, 2011). Between 2010 and 2012, under the Strengthening Environmental Protection program addressing climate change, China donated energy-efficient products to the Caribbean island of Grenada (State Council, 2014).

iii) Preferential loans play a predominant role in foreign aid. Prior to 1995, China’s assistance to Latin America consisted primarily of interest-free loans. Since the end of the 1990s, especially between 2003 and 2008, aid has been extended to preferential loans which has been granted on 23 occasions to 11 countries, including the Bahamas, Guyana, Suriname and Bolivia. As for the reduction and elimination of foreign debt, in 2006 China cancelled all the debts of Guyana (which had expired at the end of 2004) and two debts of Bolivia (which were due to expire in 2007) (State Council, 2011).

iv) Fourth, between 2003 and 2008, China has carried out several infrastructure construction projects in Latin America. Among the more than 40 works of this type carried out in 15 countries (such as Cuba, the Bahamas or Granada), the projects that stand out the most are the stadiums, convention centers, highways, hydroelectric power stations, hospitals and agricultural production centers (State Council, 2011). By 2012, China had offered concessional loans for the construction of infrastructure projects in the Caribbean nations, totaling 3 billion yuan (450 million USD) (State Council, 2014).

v) Vocational training programs have also increased, becoming an important element of China’s external assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean, focusing on sectors such as agriculture, mining, trade and administration. The implementation of these training programs has been accompanied by the participation of many young Chinese volunteers to provide assistance in diverse fields such as education, agriculture and medicine (State Council, 2011).

vi) Sixth and last, China has begun to provide assistance to local Latin American organizations: between 1998 and 2002, China made numerous donations to the Caribbean Development Bank; in July 2005, they donated computer equipment to the secretariat of the Andean Community; between 2005 and 2009, a $ 2million USD grant established the China-Organization of American States (OAS) fund; finally, in January 2009 China donated $350 USD million to the Inter-American Development Bank to support economic development and poverty reduction in Latin America and the Caribbean (State Council, 2011).

III. Motivations behind China’s aid allocation

China prides itself that its aid is unconditional, not linked to conditions normally imposed by Western donors, such as good practices, democracy and/or respect for human rights. In addition, Chinese financial assistance usually becomes readily available, without much bureaucracy (Davies, 2007). China therefore constitutes a good alternative to the donors of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC-CAD), with their very detailed bureaucratic procedures and conditionality policies. The best evidence of the preference for unconditional aid in Africa is the case of Angola, a country with very high levels of corruption, which has big difficulties to access Western aid; unsurprisingly, a major recipient of Chinese aid. In Latin America, for instance, Chinese aid to Venezuela has occupied the void generated by the shortage of loans by the World Bank. Nevertheless, unconditional aid to oil-rich countries such as Venezuela and Angola can increase the risk of political disruption and corruption (Sanderson, 2013; Ellis, 2009; Brautigam, 2009). At the same time, China’s development aid is criticized for being driven by domestic economic and political interests, to a greater extent than development assistance from traditional DAC donors.

The motives that generally move all donor countries to the granting of international aid can be grouped into three categories: (i) first, aid must depend on need of recipients; (ii) secondly, the quality of recipient’s policies and institutions could be important; and (iii) third, the donor’s own political and commercial interests play a role (Alesina & Dollar, 2000). The following paragraphs discuss these three groups of motives, focusing on the case of China.

i) In relation to poverty and development, the Ministry of Commerce (1985, p.413) stresses how its aid projects play “a positive role in the expansion of the national economies of the recipient countries and the improvement of the material and cultural life of people in these countries”. The Ministry emphasizes the idea of “mutual benefit”, in order to develop national economies of recipient countries and to promote economic growth both in China and those countries (Ministry of Commerce, 1985, p.413). The Chinese State Council underlines how the budget allocation of its aid meets the needs of the recipients, saying that China assigns primary importance to recipient countries living conditions and economic development, setting efforts to ensure that its foreign aid benefits as many people in need as possible (State Council, 2011, p.6). Brautigam (2008) points out that China uses its foreign aid to show its vision-of-self as a great power that is responsible, meaningful, fast in humanitarian aid delivery (p.7). Chinese focus on infrastructure projects could assess development needs largely neglected by DAC donors (Brautigam, 2008). However, these views contradict to a large extent what is argued by Naim (2007), that “rogue” donors like China don’t care about the long-term well-being of the population of recipient countries (p.95).

ii) The second group of motivations to donate aid is related to the quality of institutions and the governance of recipient countries. This is true when we talk about donor countries from the West, for two main reasons. First, (a) traditional donor countries use aid as an incentive mechanism for recipient countries with good institutions; for example, Öhler et al. (2012) find that aid conditional on “good governance” leads to incentives for potential recipient countries to improve their anti-corruption controls. Nevertheless, others raise questions about the effectiveness of aid for the promotion of democracy and governance (Knack, 2004, Busse and Gröning, 2009). Second, (b) traditional donors may follow a general belief that aid is more effective when it is assigned to recipients with more rigorous economic policies (Burnside and Dollar 2000), although there is not enough empirical evidence to support this relationship (Easterly et al., 2004). In contrast to the motivations of Western donors’ aid, one of the fundamental principles of China’s aid policy, and in general for its foreign policy, is the principle of non-interference in domestic affairs and respect for national sovereignty of recipient countries (Davies, 2007; Brautigam, 2008; Dreher & Fuchs, 2012). As such, Chinese aid allocation is unrelated to the form of regime and quality of governance of recipients. The Ministry of Commerce (1990, p.63) states that China has “full respect” for the sovereignty of recipient countries, and doesn’t attach any condition or ask for any privilege, maintaining the “true spirit of sincere cooperation”. Therefore, we can conclude that Chinese aid is probably not affected by the institutional and governance quality of recipient countries. Others have even argued that China, priding itself over its “no-strings-attached” approach tends to focus instead on recipients with fairly bad governance (Halper, 2010), providing assistance to unstable problematic regions and “delinquent states” (Pehnelt, 2007, p.8). In fact, China gives considerable amounts of aid to fragile states (Kaplinsky et al, 2007; Bermeo, 2011). It has been argued that the absence of any conditionality of Chinese aid could weaken democracy, governance and human rights, limit development, weaken social and environmental standards, and increase corruption (Davies 2007). According to Taylor (1998), in fact, China has opposed democratization in Africa, since it could use the failure of democratic consolidation as an argument against domestic demands for democratization. As Deng Xiaoping said, “talk about human rights, freedom and democracy is only designed to safeguard the interests of the strong, rich countries [who] practice power politics” (as quoted by Taylor, ١٩٩٨, p.٤٥٣). However, it is debatable whether China’s aid differs significantly from the distribution of DAC aid in terms of rewarding countries with better governance: earlier studies reveal a considerable difference between the rhetoric of DAC and its effective allocation of aid. For example, Germany, Finland, France, Japan and the Netherlands give the most corrupt countries more aid, not less (Isopi & Mattesini, 2010).

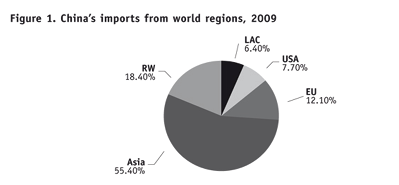

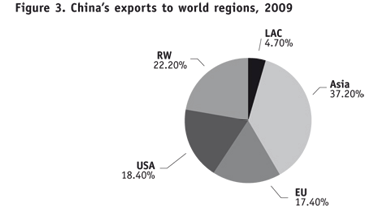

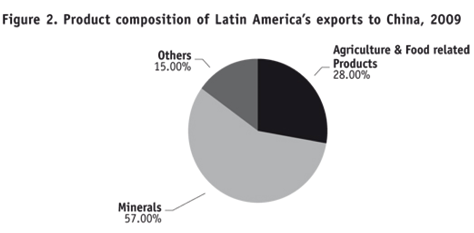

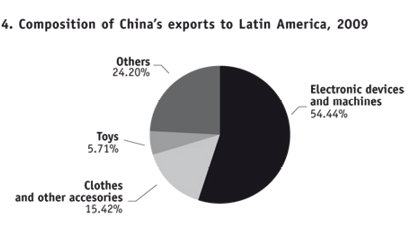

iii) Finally, the offering of foreign assistance is composed of (a) economic and (b) political motives. On the one hand, (a) in terms of its own economic and commercial interests, everything that facilitates the export of natural resources to China is seen as a central objective of its aid; China’s “insatiable needs” for resources (hydrocarbons, minerals, and timber in particular) are more often cited as trade-related reasons for Chinese foreign aid (Alden, 2005; Davies, 2007; Naim, 2007; Halper, 2010). The Chinese Ministry of Commerce is the lead agency for the provision of bilateral aid: this clearly indicates the paramount importance of trade ratios for China. Lum et al. (2009) suggest that Chinese aid to Africa and Latin America is determined by economic interests, motivated mainly by the extraction of natural resources. The vast majority of Latin American exports to China have focused on three areas: soy, metals and hydrocarbons. In fact, only three products (copper, iron and soy) account for more than half of Latin American exports to China. Chinese trade’s exponential growth has created strong ties with Latin America and potential to become a key trading partner. Brazil has become the third largest exporter of iron to China, while Chile and Peru account for 50% of Chinese imports of copper. In 2009, seeking increased oil exports, the Chinese government approved a $20 billion credit to Venezuela and purchased the Brazilian share of Repsol (a Spanish oil company) for $7.1 billion USD, with the aim of developing oil deposits in Brazil (Dowsett & Chen, 2010). Furthermore, Gallagher (2012) estimates that loans-for-oil constitute more than two-thirds of Chinese loans to Latin America. This process of increasing Chinese investments in Latin America began in 2004, when President Hu Jintao promised to invest over a 10-year period intending to reach bilateral trade of $100 billion USD. Surprisingly, this mark was surpassed much earlier, as bilateral trade had already reached $140 billion in 2008 and $261.6 billion USD in 2014. At the moment, the US remains the main economic partner of the region; China surpassed the European Union as the second largest trading partner in Latin America in 2014 (two years earlier than what CEPAL predicted in 2011), and could even surpass the US by 2030 (Hakim and Myers, 2014). Nevertheless, Latin America’s lack of diversification and dependence on products exported to China has exacerbated the region’s vulnerability to commodity price fluctuations, as up to 74% of all Latin American exports to China are primary commodities (Gallagher, 2010). In contrast, the majority of Chinese exports to Latin America are from the manufacturing sector with a strong emphasis on electronics and vehicles; such industries, as compared to commodities, are much less prone to price volatility, evidencing an asymmetric trade relationship. As some scholars put it, Chinese trade is pushing Latin America into a “raw materials corner”. More bluntly, Chinese focus on Latin American raw materials and the flood of cheap Chinese products is precluding the diversification of the exporting industries of Latin American nations, since it is more lucrative to merely sell raw materials to China than encourage entrepreneurship and diversification of the economy, thus stimulating an unfavorable “overdependence on natural resource exports”. As the NAFTA negotiator from Nicaragua put it, “China is an awakening monster that can eat us” (as cited in Gallagher & Porzecanski, 2008, p.185).

In addition to secure resources, Chinese aid is accused of directing future access to export markets and profitable investments (Davies, 2007; Lum et al., 2009). Devlin (2007) provides statistics about the one-sided relationship, describing how Chile, Argentina, and Mexico were the only Latin American countries among China’s top 40 suppliers in 2002, altogether accounting for just 1.3 percent of total imports. On the contrary, Latin America has become the most dynamic export market for Chinese products, with an annual growth of 31% between 2005 and 2010, versus 16% for the rest of the world (Toro, 2013; Smith et al., 2013; Gallagher, 2008); thus the Sino-Latin American trade is characterized by a substantial trade deficit.

Figure 5 - China-LAC bilateral trade

|

China’s exports to world regions

|

Product composition of LAC exports to China

|

|

|

|

China’s imports from world regions

|

Product composition of China’s exports to LAC

|

|

|

Source: CEPAL, 2009; Leiteritz, 2012.

Furthermore, most Chinese aid is “tied aid”, which is another indication that China uses foreign aid to improve its business opportunities (Pehnelt, 2007; Schüller et al., 2010). For instance, when China funded the construction of 2.2 billion USD dam in Ecuador, over 1,000 Chinese engineers and workers were deployed to the Latin American country, rather than hiring Ecuadorian workers (Krauss & Bradsher, 2015). The Ministry of Trade (1999) openly concluded that, through aid, Chinese enterprises entered developing countries’ markets very quickly and were welcomed by those countries’ governments and enterprises (p.75).

On the other hand, (b) regarding the political motivations of China’s aid allocation, the Ministry of Commerce (1996) openly admits that aid and subsidies are used to coordinate diplomatic work, and that building “some public institutions [...] produced great political influences” (p.70). The aid program is aimed at supporting diplomatic high - level events: for example, to achieve greater participation of heads of State in the ceremonies of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, China speeded up the implementation of the projects most valued by bilateral leaders (Ministry of Commerce, 2009, p.348). However, according to the State Council (2011), China “never uses foreign aid as a means to [...] seek political privileges for itself” (p.3). As a matter of fact, the literature has paid particular attention to the political motivation of allocating aid from China. For instance, Africa is important for China’s political agenda and building alliances, as it supported the People’s Republic to represent China at the United Nations instead of Taiwan (Davies, 2007, p.27). Taiwan, considered by China a nonaligned province, has diplomatic relations with only twenty countries, with embassies, trade agreements and foreign aid, which strengthen Taiwan’s effective sovereignty. The largest group of those countries (eleven, as shown by Table 1 below) is in Latin America and the Caribbean, particularly in Central America, which maintain this arrangement because Taiwan spends heavily to maintain it. Nevertheless, Taiwan can difficultly outspend mainland China, which uses the aid to impose its “One China policy”, rewarding countries that do not recognize Taiwan as a separate country (Taylor, ١٩٩٨; Brautigam, 2008, Rich, 2009). That has been evident in LAC, where China invested in costly projects, sometimes in exchange for ending diplomatic relations with Taiwan; Panama, has been the latest country in switching recognition from Taiwan to the PRC in June 2017. However, despite the “one China” policy, the PRC also provides aid to countries that recognize Taiwan (Davies, 2007).

Table 2 – Countries recognizing the PRC or the ROC in Latin America and the Caribbean in June 2017

|

Countries recognizing

the PRC (China)

|

Countries recognizing

the ROC (Taiwan)

|

|

Central America

|

Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama

|

El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua

|

|

Caribbean

|

Antigua & Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Cuba, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, Trinidad & Tobago

|

Belize, Dominican Republic, Haiti, St. Kitts & Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent & the Grenadines

|

|

South America

|

Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela

|

Paraguay

|

Source: Compiled by the author based on information from the Ministry of Foreign Relations of the Republic of China (Taiwan) website: http://www.mofa.gov.tw/

Finally, because of its problematic human rights record, China has supported African countries to play an important role in preventing sanctions against the Asian country (Lancaster, 2007) in organizations such as the UN Human Rights Commission. China, in fact, seems determined to increase its influence in such international organizations (Taylor, 1998), in order to “build coalitions to protect Beijing from criticism from the West” (Tull, 2006, p.460).

In summary, there are four main factors that encompass the economic and political interests of China in Latin America and the Caribbean (Ellis, 2009): (1) acquiring primary products, (2) cultivating markets for Chinese exports, (3) gaining international isolation of Taiwan, and (4) securing strategic alliance with Latin America.

However, following the win-win doctrine of Chinese foreign aid, Latin America also fulfils its own strategic interests in its relationship with China, for three reasons: (1) creating export-led economic growth, (2) attracting investment in hydrocarbon exploration and development, and (3) counterbalancing the hegemony of the United States (Ellis, 2009; Hearn & León-Manríquez, 2011).

IV. Potential developments

Chinese aid has been considered as the most “rogue” aid among new donors (Naim, 2007), since it is used to gain diplomatic and political support on the international scene, it is allocated in order to gain access to raw materials and natural resources and open new markets for its own manufactured products, and it is assigned to fragile and corrupt countries undermining the effort of western donors towards better governance and rule of law. However, aid from DAC and other emerging donors has been found to be motivated by political self-interest as well. While all donors use aid to further their strategic interests, China is more open in stressing that its aid is favoring its own model of development and that it is aimed at mutual benefit. It is clear that Chinese cooperation with LAC doesn’t follow the traditional rhetoric of giving aid on a humanitarian basis, but it privileges a South-South cooperation approach, based on the exchange of resources, technology, and knowledge between developing countries perceived as equals, and without obligations (since there is no colonial history among them). China’s commitment to such approach is underlined by the fact that the first time that Chinese Government has signed an agreement with a multilateral partner, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 2010, it has been with the aim of strengthening South-South cooperation. As president Xi Jinping himself described it, while chairing a a South-South meeting at the UN, South-South cooperation is “a great pioneering measure uniting the developing nations together for self-improvement, is featured by equality, mutual trust, mutual benefit, win-win result, solidarity and mutual assistance and can help developing nations pave a new path for development and prosperity” and “as the overall strength of developing nations improves, the South-South cooperation is set to play a bigger role in promoting the collective rise of developing countries.” Indeed, the relationship between China and Latin America and the Caribbean in the past decades can indeed be described as a win-win relation: while Latin America needs Chinese foreign aid money and needs a buyer for its abundant raw materials, China needs natural resources and wants to enter developing markets to place its manufactured products. As it has been suggested in the course of this article, LAC experimented both positive and negative impacts from Chinese foreign aid and bilateral trade. Positive impacts include an increased funding for a number of infrastructure project and increased trade revenues. However, negative impacts could potentially outweigh positive effects: the imbalances in the relationship and the fluctuations in the raw material demand and prices, show that China alone may not be enough to sustain the development of entire economies in the region, which risk falling in the “resource curse”. Chinese money also influences the stability and the transparency of the region: on the one hand, Chinese aid may help to sustain corrupt, unethical and inefficient regimes; on the other hand, it may also contribute to the stability of regimes more committed to democracy. As such, the tendencies of retrogression into undiversified and deindustrialized economies dependent on non-renewable raw resources and the increase of corruption prompted by Chinese unconditional aid and unbalanced trade, could undermine the efforts of traditional donors (i.e. World Bank and IMF) towards better governance in the region.

Some authors are optimistic (Devlin, 2007; Toro, 2013) and hypothesize that Chinese aid and trade can sustain the development of Latin America and the Caribbean, providing economic growth, a strategic economic model and a strong trade partner. The World Bank (De la Torre et al., 2011) supports the hypothesis of a sustained long-term economic growth “made in China” even after the 2008 economic crisis, assuming that Chinese growth is long-lasting and stable. In fact, the growing relation between China and LAC provides an historic opportunity to the region for unprecedented progress to rebalance its gaps in productivity, innovation, infrastructure, logistics, and capacity-building. Cooperation with China, in the context of the 2015-2019 Cooperation Plan, could lead to a rethinking of the regional industrial policy, leading to a greater processing of raw materials, better linked to manufacturing and services sectors, and fuelling intraregional trade (Leiteritz, 2012).

Others authors, on the contrary, have a more pessimistic approach, and maintain that Chinese unconditional aid and trade, while triggering short-term growths in Latin American economies, will not be able to sustain them in the long-term. Chinese “no-strings attached” approach towards developing regions is detrimental of business’s best-practices, human rights and good governance (Roett & Paz, 2008, Curran, 2016). Unconditional aid will continue to represent an alternative to conditional Western foreign aid, hindering governance reforms and allowing corruption and inefficiencies to survive, especially in resource rich countries. Furthermore, a concentration on raw resources combined with an increased competition from China in manufacturing markets could discourage innovative technologies and productivity, sparking fears of “deindustrialization” in the region, in particular in Brazil and Chile (Hearn & León-Manríquez, 2011, p.246). The deceleration of Chinese economy (which “only” grew by a 7% in 2015 and by 6.9% in 2016), slowing down Chinese demand of raw materials and causing a drop in their price, intensifies doubts about long-term sustainability of the Sino-Latin American relationship.

Conclusion

During the last decade, China has risen as a very visible actor in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). It has done so in a variety of manners, mainly through its foreign aid, its investments and its bilateral trade. The first section of this article provided an overview of the historical evolution of Chinese aid to the region, showing how Chinese cooperation, from a series of small actions directed mainly to communist countries all around the world, became a full scale worldwide aid program, active in all regions of the developing world; furthermore, it summarized the approach to cooperation with LAC for each phase. The second section of this article offered an attempt to quantify the amount of Chinese aid received by LAC as compared to other developing regions, confirming the worldwide approach of Chinese aid. It also showed that while Sub-Saharan Africa is by far the region receiving the most aid in terms of aid projects, in the last decade Latin America and the Caribbean has seen its share sharply rise in terms of amount of aid allocated, passing from less than 5% to 20% of total Chinese aid budget. The third section assessed three main group of motives which may drive China to provide aid: though the need of the recipient and the institutional characteristics of the beneficiary are not relevant, political motives such the recognition of Taiwan may have an effect; furthermore, Chinese aid is openly directed to benefit the economic and commercial interests of the donor country, especially regarding its energy and raw material needs. In fact, privileging a South-South cooperation approach (which diverges from the classical humanitarian model of aid), Chinese official policy is formally described as a win-win approach: on the one hand China strongly needs big amounts of oil and raw materials for its energy and production needs; on the other hand, LAC need a buyer for their abundant natural resources, and they also need Chinese foreign aid and investments for their development goals. Finally, the fourth section consisted in an appraisal of the potential benefits and negative impacts of the Sino-LAC relationship, finding among potential concerns the unconditionality of Chinese foreign aid and its unbalanced trade relationship with the region. In light of the strategic and economic comprehensive analysis of Chinese unconditional aid and bilateral trade to Latin America and the Caribbean, we may conclude that China certainly provides short and medium term growth to the region, but it is more difficult to talk of a long term sustainable advancement, unless LAC governments succeed in diversifying their economies, avoiding exposing themselves to drops in the price of natural resources. Undoubtedly China will be a long-lasting ally to the region and partnerships with China are not to fear; however, there is a relatively high possibility of difficult times ahead, and LAC governments need to take steps to be prepared beforehand.

References

Alesina, A., & Dollar, D. (2000). Who gives foreign aid to whom and why? Journal of economic growth, 5(1), 33-63.

Alden, C. (2007). China in Africa: Partner, Competitor or Hegemon? (African Arguments). International African Institute, Royal African Society and Social Science Research Council.

Bartke, W. (1989). The Economic Aid of the PR China to Developing and Socialist Countries, 2d ed. Munich: K. G. Saur.

Bermeo, S. B. (2011). Foreign aid and regime change: a role for donor intent. World Development, 39(11), 2021-2031.

Brautigam, D. (2008). China’s African Aid: Transatlantic Challenges, Washington, DC: The German Marshall Fund of the United States.

Brautigam, D. (2009). The dragon’s gift: the real story of China in Africa. Oxford University Press.

Busse, M., & Groening, S. (2010). Does Foreign Aid Improve Governance?

CEPAL (2011). People’s Republic of China and Latin America and the Caribbean. Ushering in a new era in the economic and trade relationship. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL, November.

CEPAL, N. (2015). Latin America and the Caribbean and China: towards a new era in economic cooperation. Available at: http://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/38197/1/S1500388_en.pdf (accessed July 2017)

Curran, J. (2016). China to the Rescue? Implications of Chinese Aid and Trade in Latin America Based on Evidence from Sino-African Cases.

Davies, P. (2007). China and the End of Poverty in Africa – towards Mutual Benefit? Diakonia, Alfaprint, Sundyberg, Sweden.

De la Torre, A., Didier, T., Calderón, C., Cordella, T., & Pienknagura, S. (2011). Latin America and the Caribbean’s Long-Term Growth: Made in China? Washington: World Bank.

Devlin, R., Estevadeordal, A., & Rodríguez-Clare, A. (2006). The Emergence of china: Opportunities and challenges for latin america and the caribbean. IDB.

Dowsett, S., & Chen, A. (2010). China’s Sinopec buys Repsol Brazil stake for $7.1 billion. Reuters, Oct 1, 2010. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-repsol-sinopec-idUSTRE6900YZ20101001 (accessed June 2017)

Dreher, A., & Fuchs, A. (2012). Rogue aid? The determinants of China’s aid allocation.

Ellis, R. E. (2009). China in Latin America: the whats and wherefores (Vol. ٤٦). Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Gallagher, K. P., & Myers, M. (2016). China-Latin America Finance Database. Washington: Inter-American Dialogue.

Gallagher, K., & Porzecanski, R. (2008). China matters: China’s economic impact in Latin America. Latin American Research Review, 43(1), 185-200.

Gallagher, K., & Porzecanski, R. (2010). The dragon in the room: China and the future of Latin American industrialization. Stanford university press.

Gallagher, K. P., Irwin, A., & Koleski, K. (2012). The New Banks in Town: Chinese Finance in Latin America. Inter-American Dialogue. Working Paper.

Gupta, S., Pattillo, C., and Wagh, S. (2006). Are Donor Countries Giving More or Less Aid? Review of Development Economics 10, 3: pp. 535-552.

Isopi, A., & Mattesini, F. (2010, March). Aid and corruption: Do donors use development assistance to provide the “right” incentives. In AidData Conference, University College, Oxford, March (pp. ٢٢-٢٥).

Halper, S. (2010), The Beijing Consensus: How China’s Authoritarian Model Will Dominate the Twenty-first Century, New York: Basic Books.

Hawkins, D., Nielson, D., Bergevin, A., Hearn, A., & Perry, B. (2010). Codebook for Assembling Data on China’s Development Finance.

Hakim, P., & Myers, M. (2014). China and Latin America in 2013. China Policy Review.

Hearn, A. H., & León-Manríquez, J. L. (Eds.). (2011). China engages Latin America: tracing the trajectory. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Kaplinsky, R., McCormick, D., & Morris, M. (2007). The impact of China on sub-Saharan Africa.

Knack, S. (2004). Does foreign aid promote democracy? International Studies Quarterly, 48(1), 251-266.

Krauss C, & Bradsher, K. (2015, July 24). China’s Global Ambitions, with Loans and Strings Attached, The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/26/business/international/chinas-global-ambitions-with-loans-and-strings-attached.html (last accessed on June 2017).

Kobayashi, T. (2008). Evolution of China’s Aid Policy, JBICI Working Paper 27, Japan Bank for International Cooperation.

Lancaster, C. (2007). The Chinese Aid System, Center for Global Development, Essay 33.

Leiteritz, R. J. (2012). China and Latin America: a marriage made in heaven?. Colombia internacional, (75), 49-81.

Lum, T. (2009, November). China’s assistance and government-sponsored investment activities in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. Library Of Congress Washington Dc Congressional Research Service.

Ministry of Commerce (1984-2001). Almanac of China’s Foreign Economic Relations and Trade, Hong Kong: China Foreign Economic Relations and Trade Publishing House.

Ministry of Commerce (2004-2009), China Commerce Yearbook, Beijing: China Commerce and Trade Press.

Ministry of foreign affairs (2008). China’s policy paper on Latin America and the Caribbean. Available at http://www.gov.cn/english/official/2008-11/05/content_1140347.htm (last accessed on June 2017).

Naím, M. (2007). Rogue Aid, Foreign Policy 159, March/April: 95-96

OECD (1987). The Aid Programme of China. OECD, Paris.

Öhler, H., Nunnenkamp, P., & Dreher, A. (2012). Does conditionality work? A test for an innovative US aid scheme. European Economic Review, 56(1), 138-153.

Pehnelt, G. (2007). The political economy of China’s aid policy in Africa. Jena Economic Research Paper, (2007-051).

Rich, T. S. (2009). Status for Sale: Taiwan and the Competition for Diplomatic Recognition, Issues & Studies 45, 4: 159-188.

Roett, R., & Paz, G. (Eds.). (2008). China’s expansion into the western hemisphere: Implications for Latin America and the United States. Brookings Institution Press.

Sanderson, H., & Forsythe, M. (2012). China’s superbank: debt, oil and influence-how China Development Bank is rewriting the rules of finance. John Wiley & Sons.

Schüller, M., Brod, M., Neff D. & Marco Bünte (2010). China’s Emergence within Southeast Asia’s Aid Architecture: New Kid on the Block? Paper presented at the AidData Conference, University College, Oxford, March 22-25.

Shinn, D. (2006). Africa, China and health care. Inside AISA, 3(4), 15.

Smith, P. H., Horisaka, K., & Nishijima, S. (2003). East Asia and Latin America: the unlikely alliance. Rowman & Littlefield.

State Council (2011). White Paper on China’s Foreign Aid, Xinhua/China’s Information Office of the State Council, available at http://www.gov.cn/english/official/2011-04/21/content_1849913.htm (accessed June 2017).

State Council (2014). China’s Foreign Aid, Beijing/China’s Information Office of the State Council, available at

http://www.china.org.cn/government/whitepaper/node_7209074.htm (accessed June 2017).

Sun, Y. (2014). China’s Aid to Africa: Monster or Messiah? The Brookings Institution, February 7, 2014, available at http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2014/02/07-china-aid-to-africa-sun (accessed June 2017).

Taylor, I. (2007). China and Africa: engagement and compromise (Vol. ١٠). Routledge.

Taylor, I. (2009). China’s new role in Africa. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Toro, A. (2013). The world turned upside down: the complex partnership between China and Latin America (Vol. ٣٤). World Scientific.

Tull, D. M. (2006). China’s Engagement in Africa: Scope, Significance and Consequences, Journal of Modern African Studies 44, 3: 459-479.

Villanger,

Watson, K. (2015), What will China’s investment do for Latin America? BBC News, July 7, 2015.