Resultado de Investigación

USAID’S Assured Assistance:

USAID’s Humanitarian Aid in Latin America and the Caribbean 2001- 2019

Asistencia asegurada de USAID:

Ayuda Humanitaria de USAID en América Latina y el Caribe 2001- 2019

Carolyn Louise Carpenter1

Copyright: © 2020

Revista Internacional de Cooperación y Desarrollo.

Esta revista proporciona acceso abierto a todos sus contenidos bajo los términos de la licencia creative commons Atribución–NoComercial–SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Tipo de artículo: Resultado de Investigación

Recibido: julio de 2020

Revisado: septiembre de 2020

Aceptado: octubre de 2020

Autores

1 Carolyn Carpenter is currently a Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TESOL) Education professor at the University of San Buenaventura in Cartagena, Colombia. She has trained U.S. Peace Corps Volunteers and teachers in development and assistance projects in Paraguay and Colombia. She holds a Master of TESOL from Boston University (USA) and Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology and Spanish from the University of Wisconsin (USA).

Correo electrónico: carolyn.carpenter@usbctg.edu.co

Orcid: 0000-0002-1315-0599

Cómo citar:

Carpenter, C. L. (2020). USAID’S Assured Assistance: USAID’s Humanitarian Aid in Latin America and the Caribbean 2001- 2019. Revista Internacional de Cooperación y Desarrollo. 7(2). 163-176

DOI 10.21500/23825014.4689

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is the largest donor of short-term humanitarian aid to Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). A quantitative analysis of USAID’s disaster relief funding for LAC from 2001-2019 was conducted to determine trends of its contracting practices and their impact on providing relief to LAC citizens. The findings demonstrate that USAID provides billions of dollars in assistance, but the results of relief projects helping individual recipients in need are ambiguous. 93% foreign aid contracts are awarded to U.S. businesses. The United States views short-term assistance programs to foreign nations as investments in the long-term growth of a globalized economy. It is recommended that the LAC for-profit and non-profit organizations follow a similar strategy and capitalize on the assured assistance of USAID.

Keywords: Foreign aid; foreign policy; disaster relief; NGO; GO; contracting.

Resumen

La Agencia de los Estados Unidos para el Desarrollo Internacional (USAID) es el mayor donante de ayuda humanitaria a corto plazo para América Latina y el Caribe (ALC). Se realizó un análisis cuantitativo del financiamiento de USAID para el alivio de desastres para LAC entre 2001 y 2019 para determinar las tendencias de sus prácticas de contratación y su impacto en la prestación de ayuda a los ciudadanos de LAC. Los hallazgos demuestran que USAID proporciona miles de millones de dólares en asistencia, pero los resultados de los proyectos a los beneficiarios más necesitados son ambiguos. El 93% de los contratos de ayuda exterior se otorgan a empresas estadounidenses. Estados Unidos ve los programas de asistencia a corto plazo a países extranjeros como inversiones en el crecimiento a largo plazo de una economía globalizada. Se recomienda que las organizaciones de LAC con y sin fines de lucro sigan una estrategia similar y capitalicen la asistencia asegurada de USAID.

Palabras claves: Ayuda exterior; política exterior; ayuda en casos de desastre; ONG; OG; contratación.

1. Introduction

The United States of America is a major contributor to humanitarian efforts around the world. The budget is set aside to assist with people who have suffered from natural disasters like tsunamis, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, and earthquakes which create humanitarian crises. Climatic change and environmental damage cause life-threatening droughts, flooding, landslides, and pollution. People lose their homes and crops, and/or they do not have access to clean drinking water, food, or medicine. The United States (U.S.) government also provides relief to citizens who are trapped in regions of political unrest, violence, and crime and are forced to migrate as refugees and seek asylum in neighboring countries.

In 2020, the total U.S. budget including all foreign and domestic programs is 1.7 trillion dollars (USAspending.gov, 2019). The 2021 budget for humanitarian assistance is 6.4 billion (ForeignAssistance.gov, 2020). The US defines foreign assistance as:

aid as given by the United States to other countries to support global peace, security, and development efforts, and provide humanitarian relief during times of crisis. It is a strategic, economic, and moral imperative for the United States and vital to U.S. national security. (ForeignAssistance.gov, 2020).

The United States supports allied or partner countries to ensure regional and global stability. In turn, the support builds countries’ economies and markets, and the United States has a moral obligation to help victims of war, violence, and natural disasters (Ingram, 2020).

Assistance or aid is categorized into long-term and short-term objectives. The long-term objective is named international development: sustainable growth of economic institutions and persons’ access to the economic system, access to a democratic political system, human development, and the reduction of global migration and refugees, poverty, conflict, and the destruction of the environment (Oxford, 1970). The short-term objective is humanitarian assistance: to save lives, lessen misery, and maintain dignity after or preparing for foreseeable natural or manmade disasters. According to the United Nations, all programs and policies should be built based on the “key humanitarian principles of: humanity, impartiality, neutrality and independence” (Bagshaw, 2012).

U.S. government foreign aid is divided into nine categories: humanitarian assistance; democracy, human rights, and governance; environment; multi-sector; peace and security; health; educational and social services; economic development, and program development (ForeignAssistance.gov, 2020). Crisis intervention is 14% of the total foreign aid budget. Its funding is distributed to multi-lateral organizations like the United Nations and International Red Cross and foreign and domestic agencies: Governmental Organizations (GOs), Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), enterprises, faith-based institutions, and universities. Additionally, the aid supports relief efforts managed by the U.S. State and Defense Departments. It also purchases U.S. agricultural goods for populations in crisis around the globe (McBride, 2008).

Most of the foreign assistance is managed by the United States Agency of International Development (USAID), a branch of the State Department, and works in over 100 developing countries worldwide. USAID works with long-term development projects and short-term relief projects divided into sectors: Global Development Lab, Agriculture and Food Security, Democracy- Human Rights and Governance, Economic Growth and Trade, Education, Environment and Global Climate Change, Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment, Global Health, Humanitarian Assistance, Water and Sanitation, and Working in Crisis and Conflict. The sectors’ work is divided into regions: Afghanistan and Pakistan, Africa, Asia, Europe, and Eurasia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Middle East (“What We Do”, 2018).

In 2019, USAID’s total budget for the world was US$39.3 billion, and US$16.8 billion was appropriated for all humanitarian assistance (USAID, 2018).The Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance defines its mission as “to save lives, alleviate human suffering, and reduce the impact of disasters by helping people in need become more self-reliant” (Humanitarian Assistance, 2020). A major recipient of funding is Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). From 2010- 2019, USAID’s partner countries in LAC are Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, and Venezuela (USAID, 2019).

At first glance, the United States seems to be a benevolent donor to its neighboring countries to the South when they are in moments of crises: natural disasters, famine, disease, conflict, and forced migration. However, it comes into question whether LAC countries pay political, economic, and social costs accepting U.S. assistance. Is the LAC forced to be an ally or partner of the United States due to fragile democracies, markets, or political stability? Is the LAC capable of taking care of its vulnerable populations in a time of disaster or crisis? Even in 2020, the assistance could be viewed as the formation of banana republics as the United States looks for cheap labor and natural resources. On the other hand, LAC may still require foreign capital and assistance to thrive (Williams, 2013).

USAID funds the polling of Latin American citizens in the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) to guide U.S. and foreign policymakers in economic and political goals. In LAPOP’s surveys called the “Americas’ Barometer,” researchers have revealed that the most important perceived problems facing Latin Americans are the economy and crime. Corruption is perceived as less of a problem since it has become normalized as a political practice. Even though the economy is not as stable as Latin Americans would have hoped, there is still a notion that national economies and personal wealth are increasing. There is a feeling of prosperity in the region. However, the reality is different from perception. In the 2010- 2012 LAPOP survey, Latin Americans felt that crime and corruption had decreased even though in some countries they had increased. Fear of crime and corruption exist, but they are considered less important than one’s personal wealth. (Segilson et al., 2012). Capitalistic economics based on the consumption of goods and services are fueled by optimism. If Latin Americans believe they are better off economically than before, they will consume more and therefore, increase their participation in the globalized economy.

All countries’ economies are strongly linked. No country in North America, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean or the Americas can develop economically on their own. The consumption of imported and exported goods produces growth. U.S. foreign policy and USAID programming are designed to ensure basic human needs are met; stability grows, economies expand, and in turn, the consumption of products increases. The investment of USAID in the LAC is a necessity for economic prosperity in the United States and all its partner countries. Long-term development or short-term aid both promote goodwill, security, and stability which create a perception of wealth in the Americas. USAID exists to keep this estimation alive potentially permitting all Americans to prosper. Therefore, USAID will assure funding for long-term development and short-term assistance programs to LAC partner countries. This article will examine U.S. short-term humanitarian assistance in times of natural and manmade disasters or crisis. The foreign assistance policy of the United States is tactical, designed to strengthen global economies and therefore, the U.S. economy. USAID’s partner countries’ policymakers, businesses, and non-profit organizations should exploit the humanitarian, economic, and political benefits when receiving short-term assistance as the U.S. does when donating it.

2. Methodology

The focus of this study is short-term humanitarian assistance projects due to its urgency, immediate impact on a region, and the ability to measure trends and implications. The effectiveness or success of long-term development projects is harder to determine because of their duration: modification in funding (donors, recipients, and amounts) and change in foreign and domestic political leaders, policies, and interests over time (Elayah, 2016). Due to the complexity of the social, political, and economic issues fueling humanitarian assistance in LAC, the research method is designed to provide both a description and explanation of the phenomena using both qualitative and quantitative data. (Glicken, 2003). In this study, historical and current international organizations and U.S. policies, guidelines, and laws are extensively outlined. Data from U.S. government databases on the funding of assistance projects and programs, official U.S. financial and procedural audits of those projects and programs, as well as official criteria and approvals from 2001- 2019, are analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively to provide a US view of its work in the LAC region. As a result, the trends and implications of humanitarian assistance from 2001- 2019 can be determined. The research of documents starting from 2001 was based on historical events in the region. After the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington D.C on September 11, 2001, there was a major shift in U.S. foreign policy and its long and short term aid to create stability and safety globally and therefore, reduce the growth of extremist or terrorist groups who threatened the United States and its allies. In addition, there has also been an increase in aid given directly to the U.S. and foreign independent contractors: NGOs, private enterprises, and faith-based and multi-lateral organizations from 2001- 2019. At the beginning of the research process, the assumption is that private contractors were used to improve efficiency and effectiveness and reduce the potential of money being squandered in governmental bureaucracy and corruption scandals.

The selection of summaries of financial and funding reports and raw data are mainly from the U.S. government websites and databases due to their accessibility to the public. All U.S. government agencies, including USAID, have all their project summaries and financial reports published online. Raw data was also downloaded and analyzed systematically without prejudice or allegiance to a U.S. or foreign agency or office. During preliminary research, it was discovered that LAC project programming and funding reports from foreign agencies who received aid were paid for by USAID. Therefore, they reflected the U.S. reports’ findings. However, despite the biased view of foreign reports, they provide a window into the world of humanitarian assistance and its trends, actors, and effectiveness can be deduced. Expectantly, the understanding of the USAID’s policy and funding of humanitarian assistance will guide recipients in how to capitalize on short-term aid from the United States.

The theoretical framework of the study is based on international law and guidelines for effective international development and aid. In the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human rights, Article 3 states “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person” (General Assembly, 1948). Therefore, all United Nations (UN) members must ensure that their citizens are able to survive and are secure from any disaster. The UN’s Committee of Economic, Social, and Cultural rights further states that if a country cannot assist its citizens in a time of crisis, it must find an entity that can (Heath, 2011, p.447). Now that UN member states are legally bound to provide humanitarian assistance, the most effective aid delivery system comes into question. For this study, the theory that the recipient country or community knows what the best plan is to aid it in a time of crisis is applied (Sachs, 2006). Countries should have the potential natural and manmade disasters mapped out and should calculate which of their populations are most at-risk. They should also determine to what extent and when their regions will be affected. The recipient country must adhere to international law: humanitarian assistance is a basic human right and if the country cannot honor that right, the country must cooperate and find international entities to protect and preserve the lives of its citizens.

3. Discussion

A. United Nations and Humanitarian Assistance

To begin the discussion of assistance, an overview of the largest provider of humanitarian assistance in the world, the United Nations (UN), is given to understand the position of USAID in Latin America and the world. The UN has served as a diplomatic forum to organize and aid its 193 state members since 1945. After the devastation of World War II, world leaders saw the need to assure political and economic stability throughout the world. Just in 2020 alone, it is predicted that 168 million people or 2% of the world’s population will need humanitarian assistance in the areas of housing, food, healthcare, education, and protection. LAC has been a concern due to its social disturbances, and emerging democratic process, and economic markets. It is also the second most vulnerable region to natural disasters due to environmental conditions and climate change in the world (OCHA, 2019). The UN is designed to help mitigate these humanitarian issues.

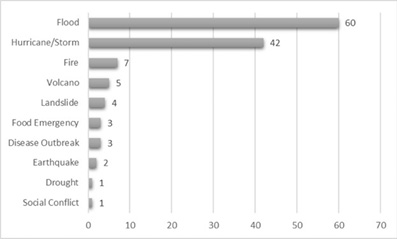

The UN divides its member nation-states into regions. The Latin American and Caribbean Group (GRULAC) consists of 33 member states which are 17% of total member nations (United Nations DGACM, n.d.). Due to its size and social, political, and environmental vulnerability, the UN creates programs that respond specifically to the humanitarian needs of GRULAC, the second- most disaster-prone region in the world (OCHA, 2019). The Pacific and Andean regions are home to the Ring of Fire where volcanic eruptions and earthquakes have destroyed rural and urban centers (See Figure 2). In addition, the effects of climate change have created many adverse results in the region. Extreme weather variation has caused lower than expected rates of food production, and higher rates of famine and economic strife for farmers and consumers. Farmers are constantly at risk of losing their crops and consumers must pay higher prices for their food due to lower supply. Unseasonably high temperatures and low-rainfall cause also cause wildfires. Manmade fires lit to prepare fields for farming and ranching have also increased. Finally, the largest problem is flooding caused by excessive rainfall and deforestation (See Figure 2). Recently, the violence triggered by rebel groups, drug cartels, and autocratic leaders has caused great social and economic instability. Colombia’s 50 year-long armed conflict and fight for drug production territory have caused “by far the biggest humanitarian catastrophe of the Western Hemisphere” (Canby, 2004, p.31). Central American communities have also been devastated by drug-related crime and violence and are migrating to Mexico and the United States. In Venezuela, scarcities of food and medicine and extremely high rates of inflation have caused over 4.5 million people to migrate to neighboring countries and, as far as, North America and Europe. By 2021, 500 thousand more Venezuelan citizens are expected to leave their country. Currently, it is one of the largest migration crises in the world (OCHA, 2019).

The UN is designed to discuss, plan, and provide assistance to such grave and complex situations and claims that most humanitarian crises (political, economic, and climatic) can be predicted. This theory allows for a policy of “anticipatory action… a pre-agreed action plan that outlines feasible an impactful intervention; pre-arranged contingency financing that is predictable and fast” (OCHA, 2019, p.82). They are always “early warning signs” and “forecasting tools” that can predict forthcoming disasters (OCHA, 2019, p.83). Good planning and budgeting create efficiency in project execution and spending. The Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) and Country-based Pooled Funds (CBPF) are reserves that can be used in critical situations in a timely and cost-efficient matter. In 2019, over US$494 million were designated quickly to overt or relieve humanitarian calamities (OCHA, 2019, p. 84). Predictions of regions’ vulnerabilities, pre-approved plans, and budgets, and audits of every contribution and expenditure improve living standards, increase financial stability, and provide protection with military support. It also motivates donor nations, like the United States, to contribute to future disasters. The anticipatory action produces the efficiency required for effective humanitarian aid results.

B. USAID’s Historical and Future Objectives

U.S. foreign policy is congruent with the UN’s guidelines of providing humanitarian assistance and has directed USAID’s global initiatives from its start in 1961 until today. On November 3, 1961, President John F. Kennedy inaugurated USAID. Kennedy voiced to the world that the United States has a moral obligation to provide aid. In his speech he stated:

There is no escaping our obligations: our moral obligations as a wise leader and good neighbor in the interdependent community of free nations – our economic obligations as the wealthiest people in a world of largely poor people, as a nation no longer dependent upon the loans from abroad that once helped us develop our own economy – and our political obligations as the single largest counter to the adversaries of freedom (USAID History, 2018).

Kennedy presents the United States as an intelligent and economically strong country that is adept at assisting in times of crisis. He echoes upon prior policies in the 1950s which aimed to strengthen foreign economies and allow them to grow under capitalism. The United States wanted to expand its export market and reduce foreign countries’ interest in Communism. In the 1960s, long-term development was USAID’s focus. However, in the 1970s there was a shift to concentrate on basic human needs: food, health, education, and shelter. It also began family planning programs to control population growth. In the 1980s, it changed course to building foreign economies with large-scale efforts to provide employment opportunities and increase international market competitiveness. After the fall of Communism in 1989 and the threat of the USSR infiltrating the free market system had diminished, USAID shifted its focus, once again, to countries becoming economically independent and being able to take care of its citizens in times of crises and the long-term. In the 2000s, USAID is working on being more fiscally responsible to U.S. taxpayers. It needs more concrete results and efficiency to justify every dollar spent. As a result, it hires U.S. and foreign contractors and sub-contractors (NGOs) to conduct the work abroad. Its reduction in bureaucracy decreases its spending, but the programs’ effectiveness is harder to determine (USAID History, 2018).

After looking at a historical overview of USAID’s goals, one of its original objectives still rings true today as USAID’s director, Mark Green (2018) stated “foreign assistance must always serve American interests” (Wong, 2018). In fact, in all the annual reports written from 2001- 2019 for the U.S. Congress examined, the agency directors reiterate that USAID augments U.S. economic growth. All countries that receive assistance from USAID will become more self-reliant politically and economically. As countries become more independent and wealthier, they can buy more U.S. exports. From 2008- 2018, 66% of the growth attributed to U.S. exports was because of trading with USAID partner countries. The rise in exports was vital in pulling the United States out of the 2008 recession. In 2015 alone, 11.5 million jobs were created due to U.S. exports. Almost 95% of the world’s consumers and 80% of the world’s purchasing power are in foreign countries. Therefore, supporting partner countries’ economies that consume U.S. exports is of uttermost importance (Fox & Broughton, 2018).

The continuation of future foreign assistance is guaranteed by the U.S. State Department and USAID. They have outlined in their Joint Strategic Goals for 2018 to 2022 (USAID, 2018, p. 3) the plan to foster stability, diplomacy, and economic growth around the world.

Table 1. U.S. State Department and USAID Joint Strategic Goals 2018 to 2022

Source: Official USAID and State Department Document (USAID, 2018)

The goals demonstrate that stability, diplomacy, and wealth are highly connected and cannot be separated from one another. In the name of democracy, the U.S. Secretary of State, Rex W. Tillerson, states that the U.S. national and economic security are currently at risk and the U.S. “must leverage America’s competitive advantage to achieve economic growth and job creation” (USAID, 2018, p.11). These goals are being strategically implemented in all LAC countries today and will continue to do so until a partner country refuses funding from USAID or the State Department and ends diplomatic ties.

C. USAID and Humanitarian Assistance in LAC

In the LAC region, USAID is the greatest contributor of humanitarian assistance before and after natural and manmade disasters. The USAID Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance is mainly responsible for the distribution and management of funds to the Americas (See Figure 1). From 2004- 2013, USAID provided more than US$980 million in humanitarian aid and disaster prevention to LAC partner countries (USAID, 2014) due to the high number of emergencies caused by mostly flooding, severe storms such as hurricanes, wild and manmade fires, earthquakes, and volcanos (See Figure 2).

Figure 1. USAID Map: Disasters in Latin American and the Caribbean in 2019

Source: Image from USAID.gov (2020).

There is also been aid given during socio-political phenomena such as violence and migration due to political unrest, authoritarian governments, and illicit drug production and trafficking. The benevolence of the United States is considered one of its core values, but also the instability of any kind is harmful to trade. A country suffering from turmoil is not in conditions to consume U.S. products. Its citizens are simply trying to survive. USAID provides food, shelter, water, and health services in a disaster quickly, so the partner country can return to its economic activities such as importing U.S. products and exporting products to the United States as soon as possible. (Fox & Broghton, 2018).

Figure 2. Number and Type of Disasters Declared in LAC 2004- 2013

Source: USAID.gov (2020).

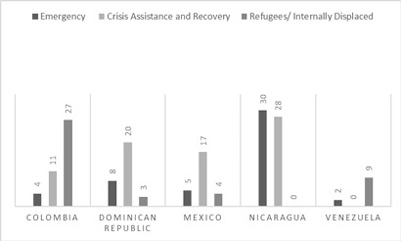

Figure 3. USAID Humanitarian Assistance Frequency from 2001- 2019

Source: Customized figure developed from the USAID database (https://explorer.usaid.gov/) (2020).

Figure 3 represents a sample from LAC countries representing the regions of the Americas: North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean. From 2001 -2019, each region has received funding for emergency, crisis and recovery, and refugees/internally displaced assistance. Emergency assistance provides basic humans needs. Crisis Assistance and Recovery is funding used for finding permanent solutions to health, education, and housing. Refugee and Internally Displaced is both for immediate and continual aid for people forced out of their homes or countries due to violence or lack of economic opportunity. For example, Nicaragua has received emergency and crisis assistance due to natural disasters such as flooding and drought. While Colombia has received assistance due to internally displaced citizens because of the violence caused by armed conflict. Displaced Venezuelans are in dire need of food, shelter, medicine, and employment and have migrated to other regions.

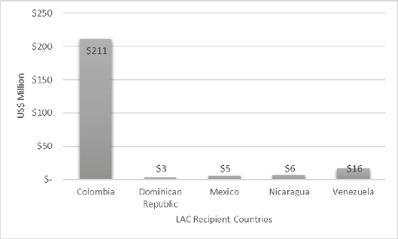

As shown in Figure 4, Colombia is a special USAID member in LAC. It has been one of the largest beneficiaries of the region in the 2000s due to its location, potential trading power, and threats to its citizens’ security. Colombia is strategically located in South America with two modern ports in the cities of Cartagena on the Caribbean and Buenaventura on the Pacific Ocean. Both ports have proximity to the Panama Canal, a vital waterway for world trade. Colombia also borders Venezuela which since the presidency of Hugo Chavez (1999- 2013) and current president, Nicolas Maduro, has become an increasing economic and political danger to the United States and Latin America. Its presidential policies and the U.S. sanctions in reaction to Maduro’s policies have caused an economic and humanitarian crisis that has paralyzed the once-prosperous nation and major U.S. trading partner. Its citizens are forced to flee into neighboring countries such as Colombia. By 2018, an estimated 3 million Venezuelans left their country, and the United States gave 96 million dollars in food and health aid mostly to Colombia to aid the migrants. An estimated 1.4 million Venezuelans will have migrated to Colombia by the end of 2020 (Wong, 2018).

Figure 4. USAID Humanitarian Assistance 2001- 2019

Source: Customized figure developed from the USAID database (https://explorer.usaid.gov/). (2020).

Colombia is classified by USAID as an “upper middle income” country which means it has great potential buying power (Office of the Inspector General, 2018). It ranks the same as Mexico and Brazil economically which means US companies see its potential and want to invest in the country’s capital and companies. Finally, Colombia is also a special case in Latin America due to its history of armed conflict against rebel forces for the past 50 years. The United States developed Plan Colombia in 2000 to aid in the areas of security, democracy, justice, environmental protection, job creation, human rights, land rights, and protection of minorities: Afro-Colombian and indigenous groups. The majority of Plan Colombia’s budget, an average of US$540 million a year, was for military support and coca leaf eradication by fumigation (USAID, 2016). However, USAID had funding of its own and was one of the key distributors of humanitarian services. Colombia received over US$200 million from 2001- 2019, far greater than any other LAC nation represented (See Figure 4).

D. Trends in Humanitarian Assistance Delivery in LAC

Since 2001, the trend in delivering humanitarian assistance is to reduce government to government donations and to increase private contractors to deliver goods and services for humanitarian assistance. Private firms are considered more efficient and cost-effective and service delivery inefficiency is considered a major problem in the United States and Latin America. The perception is that when LAC countries receive monetary or goods donations, they are lost in governmental bureaucracy, and services are not delivered at all, only partially delivered, or delayed. Vulnerable LAC populations may not receive the aid they need promptly and suffer while governments develop ways to deliver services or simply do not deliver them at all. The delivery process may be considered corrupt or dysfunctional.

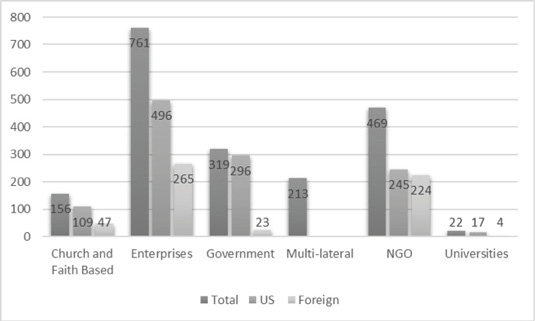

To combat corruption and bureaucracy and be in accordance with the U.S. State Department and USAID Joint Strategic Goal 2.3 (See Table 1), most USAID contracts are not given to US or foreign governments. However, when a contract is won by a government, the United States receives 93% of the contracts. Only 7% of USAID funding is given to LAC governments. The majority of awards go to for-profit enterprises. They are awarded 39% of contracts with 65% of them going to U.S. businesses. Next, are NGOs which win 24% of contracts are more balanced with 52% from the U.S. and 48% foreign. The rest of the contracts are given to multi-laterals like the United Nations and the International Red Cross, church or faith-based groups, and universities. Contracts awarded to church or faith-based groups have raised concerns. Even though they only are 8% of USAID’s awarded contracts, federally funded programs are not to endorse or favor any particular religion (Marsden, 2012). However, USAID claims that religious organizations that are being contracted only provide services that do not require recipient populations to participate in any religious acts.

Figure 5. USAID Humanitarian Assistance 2001- 2019: Number of Contracts Per Type of Recipient

Source: Customized figure developed from the USAID database

(https://explorer.usaid.gov/) (2020).

The largest criticism of USAID’s humanitarian assistance is in the United States, where accountability and justification for spending U.S. tax dollars are under constant scrutiny. Even President Obama (2009) worried that most of the USAID contracts were going to U.S. companies and the budget was being spent on administrative costs such as offices, housing, transportation, and payroll. The 1933 Buy American Act designed to ensure U.S. products were bought is used to justify contracting domestic firms for USAID projects (Roberts, 2014). However, the firms’ promised direct services may not be exactly what USAID, taxpayers, or the recipient LAC countries expected.

Humanitarian assistance spending may be dedicated to overhead more than services rendered. Missing and/or unspecific data and undisclosed contract terms make the task of figuring out where the funding is being spent exceedingly difficult (Roberts, 2014). On the publicly accessible official U.S. databases (foreignassistance.gov; explorer.usaid.gov) spending amounts, suppliers, and names and types of assistance projects are available to the public, but the specifics of each contract and spending per item per contract are not noted. Even professional auditors have trouble deciphering where the funding is being spent exactly. The U.S. Office of Inspector General (OIG) conducted an audit of USAID expenditures from 1999- 2019. A large percentage of projects were marked as having unsatisfactory contract terms, project management and/internal controls, coordination among development partners and/or operations, employee training, and compliance with regulations or procedures. There were also questionable costs, unreliable data, and suspected fraud (Office of Inspector General, 2010). The result is that it is difficult to determine exactly what the money for humanitarian assistance is being spent on. Therefore, it is extremely easy to overspend on overhead costs, misuse funds, and reduce the number of direct services being distributed to vulnerable populations.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

The ideal result for short-term humanitarian assistance in a time of crisis is that all parties benefit: the donors (government and its citizens) and the recipients (governments and its citizens). If a population is devastated by a natural or manmade disaster whether it be an earthquake or violence, economic prosperity is not possible. Humanitarian assistance is needed to relieve the short-term negative effects on multiple levels. The first level is the immediate outreach needed in an emergency such as a landslide or earthquake. The next one is to provide short- term healthcare, shelter, and food to deal with urgent cases after the disaster. Finally, there are longer-term solutions that are put in place to secure stability. This process leads to economic revival which causes a nation, region, continent, and, in turn, the world to prosper and develop. The United States and its agency USAID depend on this model of globalized prosperity. Global wealth creates U.S. wealth and vice versa. President Kennedy’s original idea that the onus of international goodwill is on the United States still exists due to its economic and political power. The United States has the financial resources and political connections to provide humanitarian assistance in all major disasters. It continues to provide these services for the good of all the world’s citizens and their personal wealth.

The problem lies when USAID, recipient countries, private contractors confuse the intentions of donated dollars and use the funding for temporary financial gain and/or political clout. Humanitarian assistance is designed to bring safety, security, and healthcare to a region acutely directed by a disaster for it to get back to normal or to participate in daily activities that stimulate the economy. The buying and selling of goods are what a capitalistic-based economy needs to thrive. When that stops due to a disaster, the local economy stops, and its effects echo throughout the world. USAID wants to reduce the ripple effect. When all the countries of the Americas function at full-strength, the United States prospers and so does Latin America and the Caribbean. When this fact is distorted by corruption, bureaucracy, political in-fighting, and violence, no country prospers to its potential.

The recommendation for LAC countries is to continue to receive humanitarian assistance from USAID as they have done since 1961. The assistance is not a donation; it is an investment. Human assistance can be painted as a benevolent gift to taxpayers and recipients of aid. The political spin of humanitarian efforts as charity is good for elections and attitudes towards democracy. However, the U.S. government understands the importance of investment in a region. The feeling of safety and stability brought by humanitarian assistance creates optimism in a country or region in crisis. Communities are more inclined and capable to participate in local, regional, and international markets and, in the end, all foreign and domestic economic indicators rise. The United States of America is profiting from all its investments including humanitarian assistance. Now, it is time for Latin America and the Caribbean to do the same and become even wealthier and more competitive neighbors.

5. References

Canby, P. (2004, August 16). Latin America’s Longest War. The Nation, pp. 33–38.

Bagshaw, S. (2012, June 1). OCHA Message on Humanitarian Principles. Retrieved April 25, 2020, from https://www.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/OOM-humanitarianprinciples_eng_June12.pdf

Babbie, E. (2002). The Basics of Social Research, 2nd edn. Southbank: Thomson Wadsworth

Defining humanitarian assistance. (n.d.). Retrieved March 20, 2020, from http://www.globalhumanitarianassistance.org/data-guides/defining-humanitarian-aid

Elayah, M. (2016). Lack of foreign aid effectiveness in developing countries between a hammer and an anvil. Contemporary Arab Affairs, 9(1), 82–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/17550912.2015.1124519

ForeignAssistance.gov. (2020). Retrieved March 7, 2020, from https://www.foreignassistance.gov/#download

Fox, L., & Broghton, R. (2018). Shared Interest: How USAID Enhances U.S. Economic Growth. Retrieved from https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1870/FINAL_Version_of_Shared_Interest_6_2018.PDF

General Assembly (1948, December 10). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved April 5, 2020, from http://www.un.org/en/udhrbook/pdf/udhr_booklet_en_web.pdf

Heath, J. B. (2011). Disasters, relief, and neglect: the duty to accept humanitarian assistance and the work of the International Law Commission. Journal of International Law and Politics. 43: 419–47

Glicken, M. D. (2003). Social Research: A Simple Guide. Boston: Pearson Education

Humanitarian Assistance. (2020, April 17). Retrieved April 17, 2020, from https://www.usaid.gov/humanitarian-assistance

Ingram, G. (2020, January 31). What every American should know about US foreign aid. Retrieved February 7, 2020, from https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/votervital/what-every-american-should-know-about-us-foreign-aid/

Latin America and the Caribbean: Where We Work. (2019, October 18). Retrieved February 2, 2020, from https://www.usaid.gov/where-we-work/latin-american-and-caribbean

Marsden, L. (2012). Bush, Obama and a faith-based US foreign policy. International Affairs, 88(5), 953–974. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2012.01113.x

McBride, J. (2018, October 1). How Does the U.S. Spend Its Foreign Aid? Retrieved March 23, 2020, from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/how-does-us-spend-its-foreign-aid

Obama, B. (2009). Interview by AllAfrica.com, July 2, 2009. Retrieved April15, 2020 from http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/interviewpresident-allafricacom-7–2-09

OCHA (2019, December 5). Global Humanitarian Overview 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020, from https://data2.unhcr.org/es/documents/details/72717

OED Online. Oxford University Press, September 2016. Web. 26 February 2020. Available at: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/us/banana_republic

Office of the Inspector General. (2010). Humanitarian Assistance Programs of U.S. Agency for International Development: Audit and Investigative Findings Fiscal Years 1999–2009. Retrieved from shorturl.at/iGLQ8

Oxford Department of International Development. (1970, April 8). Retrieved January 31, 2020, from https://www.qeh.ox.ac.uk/

Roberts, S. (2014) Development Capital: USAID and the Rise of Development

Contractors. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 104:5, 1030-1051. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2014.924749

Sachs, J. 2005. The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time. New York: Penguin

Segilson, M. A., Smith, A. E., & Zechmeister, E. J. (Eds.). (2012). The Political Culture of Democracy in the Americas, 2012: Towards Equality of Opportunity. Retrieved from https://www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/ab2012/AB2012-comparative-Report-V7-Final-Cover-01.25.13.pdf

UNITED NATIONS DGACM. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.un.org/depts/DGACM/RegionalGroups.shtml

USAID. (2016). USAID Assistance for Plan Colombia Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1862/Plan%20Colombia%20fact%20sheet_020816.pdf

USAID. (2018). Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 Development and Assistance Budget. Retrieved from https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1869/USAID_FY2019_Budget_Fact-sheet.pdf

USAID. (2018). Joint Strategic Goals for 2018 to 2022. Retrieved from https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1870/JSP_FY_2018_-_2022_FINAL.pdf

USAID. (2019). Latin America and the Caribbean Humanitarian Assistance in Review Fiscal Years (FYs) 2010 – 2019. Recuperado de https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/USAIDDCHA_LAC_Humanitarian_Assistance_in_Review_-_FY_2010-2019.pdf

USAID History. (2019, May 7). Retrieved April 7, 2020, from https://www.usaid.gov/who-we-are/usaid-history

USAspending.gov. (2019, December 31). Retrieved March 2, 2020, from https://www.usaspending.gov/#/explorer/budget_function

U.S. Government Accountability Office, “PLAN COLOMBIA: Drug Reduction Goals Were Not Fully Met, But Security Has Improved.”

What We Do. (2018, February 16). Retrieved February 5, 2020, from https://www.usaid.gov/what-we-do

Wong, E. (2018, November 3). U.S. Continues Giving Aid to Central America and to Millions of Venezuelan Refugees. Retrieved April 5, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/03/us/politics/trump-aid-refugees-migrants.html

Williams, Theodore. (2013, November 21). Where did banana republics get their name? Retrieved April 5, 2020, from https://www.economist.com/the-economist explains/2013/11/21/where-did-banana-republics-get-their-name

Zechmeister, E. J. (2012). The Political Culture of Democracy in the Americas, 2012: Towards Equality of Opportunity. (M. A. Segilson & A. E. Smith, Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/ab2012/AB2012-comparative-Report-V7-Final-Cover-01.25.13.pdf