OPEN ACCESS

OPEN ACCESS

Recent Trends of Low-Skilled Nepalese Women’s Migration to India

Tendencias recientes de la migración de mujeres nepalesas poco cualificadas a la India

Resultado de Investigación

Dr Dinesh Poudyal, Nandita Khadgi, Sushila Bajracharya & Dinesh R. Bhuju

Authors

Dr Dinesh Poudyal Goldsmiths University, London. PhD in Sociology from Goldsmiths University, specialising in International Migration and Integration.

E-mail: dpoud001@gold.ac.uk

Nandita Khadgi MICD, Mid-West University, Nepal. Faculty. Research interest: Migration and refugees, Regional security and Trans-Himalayan connectivity.

E-mail: nanditakhadgi21@gmail.com

Sushila Bajracharya Resources Himalaya Foundation, Nepal. Research Associate.

E-mail: sushilabajracharya@yahoo.com

Dinesh R. Bhuju MICD, Mid-West University and Resources Himalaya Foundation, Nepal. Professor.

E-mail: dinesh.bhuju@mu.edu.np

Cómo citar:

Poudyal, D., Khadgi, N., Bajracharya, S. & Bhuju, D. R. (2024). Recent Trends of Low-Skilled Nepalese Women’s Migration to India. Revista Internacional de Cooperación y Desarrollo. 11 (2), 21-33

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21500/23825014.7052

Copyright: © 2024

Revista Internacional de Cooperación y Desarrollo.

Esta revista proporciona acceso abierto a todos sus contenidos bajo los términos de la licencia creative commons Atribución–NoComercial–SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Tipo de artículo: Resultado de investigación

Recibido: julio de 2024

Revisado: septiembre de 2024

Aceptado: octubre de 2024

OPEN ACCESS

OPEN ACCESS

Abstract

The global migration phenomenon, particularly among working class women, has been accelerated in recent decades, with a noticeable increase observed since the early 2000s. This trend has significantly shaped the migratory patterns of Nepalese women, particularly in their movement toward India. To understand these shifts, a comprehensive survey was conducted across seven different bordering regions, by comprising interviews with 102 Nepalese women. Analysis of the survey data revealed that despite facing challenges, such as poor working environments, inadequate residential conditions, and feelings of insecurity, a majority of Nepalese women still opted to migrate to India looking for better job opportunities. Furthermore, the data uncovered a strong desire among these women to overcome gender roles and disparities. While variations existed in certain findings, by overarching similarities were observed in migration motives and socio-economic statuses. This study serves to highlight the pressing need for policy interventions, which are aimed at promoting gender equality and economic empowerment within Nepal in order to alleviate the migration pressures faced by its female population.

Keywords: Low-skilled; Female; Migration; Nepal; India.

Resumen

El fenómeno migratorio mundial, especialmente entre las mujeres de clase trabajadora, se ha acelerado en las últimas décadas, observándose un notable aumento desde principios de la década del 2000. Esta tendencia ha influido significativamente en las pautas migratorias de las mujeres nepalesas, sobre todo en su desplazamiento hacia la India. Para comprender estos cambios, se llevó a cabo una encuesta exhaustiva en siete regiones fronterizas diferentes, mediante entrevistas a 102 mujeres nepalesas. El análisis de los datos de la encuesta reveló que, a pesar de enfrentarse a problemas como un entorno laboral deficiente, condiciones de vivienda inadecuadas y sentimientos de inseguridad, la mayoría de las mujeres nepalesas optó por emigrar a la India en busca de mejores oportunidades laborales. Además, los datos revelaron un fuerte deseo entre estas mujeres de superar los roles y las disparidades de género. Aunque hubo variaciones en algunas conclusiones, se observaron similitudes generales en los motivos de la migración y la situación socioeconómica. Este estudio sirve para poner de relieve la acuciante necesidad de intervenciones políticas dirigidas a promover la igualdad de género y el empoderamiento económico en Nepal, con el fin de aliviar las presiones migratorias a las que se enfrenta su población femenina.

Palabras clave: Baja cualificación; Mujer; Migración; Nepal; India.

1. Introduction

Arguably, migration is gendered. However, until the 1970s, most research and publications on international migration focused on male migrants, exclusively and women remained invisible (Duda-Mikulin, 2013; Purkayastha, 2005). Yet, along with the growing trend of industrialization and the need for a mass labor supply, women’s participation in the wage labor market began to be recognized, and since then, there has been a significant presence of women in global migration (Aziz, 2015; Duda Mikulin, 2013; Kofman, 2005). After the late 80s, this trend proliferated in the European labour market, where women’s migration gained strong recognition. Especially since the 2000s, the increase in female labor migration has also become more complex, intersectional, and global in scale, by attracting considerable attention from academics and policy sectors (Aziz, 2015; Ballarino and Panichella, 2017; Kofman and Raghuram, 2006).

Recently, women’s participation in migration has emerged as a significant aspect of international migration, by playing a crucial role in shaping the global demographics of the immigrant population (Kofman and Raghuram, 2006; Raghuram, 2008). The 21st century has witnessed a progressive change as women have increasingly ventured into sectors traditionally dominated by men, such as technology, healthcare, engineering, and academia (Kofman and Raghuram, 2006; Purkayastha, 2005). According to recent data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM), in 2022, women and girls accounted for 49% of all international migrants. In some cases, particularly in more developed regions, the share of women among international migrants reached as high as 51%. This indicates that women made up approximately half of the estimated 280 million individuals engaged in international migration worldwide during that period. The statistics highlight the importance of considering gender dynamics in the context of international migration. By considering gender perspectives in migration composition, many scholars have argued that women’s participation in international migration has substantially shaped migratory patterns and their associated social, economic, and cultural implications (Kofman, 2005; Raghuram, 2008). Thus, in light of the changing landscape of gender migration, the current study has explored the ongoing trends of Nepalese women’s venture in low-skilled labor market in India and overall socio-economic outcomes.

2. A Snapshot of Nepalese Women’s Participation in International Migration

Considering women’s labor migration as a global phenomenon, especially at the beginning of the new millennium, South Asian women also began to participate in this trend, by influencing Nepalese women in seeking migration opportunities to the neighboring nations, especially to India. In the context of South Asia, the report highlights the changing trends in this region as the percentage of women among international migrants has experienced a remarkable increase. Specifically, the figures demonstrate a rise from 46,7% to 48,3% in recent years. However, according to the Nepal Labor Migration Report, the share of Nepalese women accounted for only 8,5% in this period (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Nepal, 2020). Behind this lower proportion, many socio-cultural, gender-biased cultural norms, political, and Nepalese labor migration policies have played key roles.

In Nepal, predominant patriarchal norms and cultural limitations significantly restrict women’s opportunities for independent migration for work (Bhadra, 2007). Traditional beliefs often dictate that women should prioritize domestic responsibilities over pursuing professional opportunities outside their homes. This societal framework not only reinforces gender roles, but also contributes to a lack of education and skills development among women, further limiting their employment prospects (Maslak, 2003). As a result, many Nepalese women find themselves confined to domestic work within the country, which is often undervalued and lacks formal recognition or financial security. This restricted view of women’s roles not only perpetuates economic dependency, but also stifles their potential for personal and professional growth. Consequently, while some women aspire to seek job opportunities abroad, the prevailing cultural attitudes and systemic barriers often prevent them from doing so, reinforcing a cycle of limited agency and restricted mobility in their pursuit of economic independence.

Various socio-cultural factors substantially limit the educational opportunities available to Nepalese girls. The Multiple Indicators Cluster Survey of 2019, jointly conducted by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) and UNICEF, highlights the noticeable gender disparity in education access among Nepalese girls (Maslak, 2003; Maharjan, 2023). The report also highlights a concerning trend as girls move into higher education levels. Particularly in rural and economically disadvantaged areas, girls face higher barriers to attending upper basic and secondary schools. Our recent survey also supports these findings. This gender-biased situation has been fueled by factors, such as conflict, poverty, child labor, child marriage, and gender-based violence, all these factors hindering girls’ access to education. To put it briefly, we can argue that the scarce opportunities for Nepalese women, specifically intersectionality of gender role in terms of education and migration can be attributed to several factors.

Along with these, particularly, in traditional patriarchal families lack confidence and comfort by allowing their daughters to migrate abroad alone, by citing concerns about their abilities, safety, and security. Although a notable shift has recently occurred, with many women participating in international migration (Ewa Duda Mikulin, 2013; Mishra, 2022; Raghuram, 2008), especially, Nepalese women’s independent migration lacks freedom of patriarchal hierarchy (Mishra, 2022). This trend has resulted in women being categorized as dependent or family migrants despite possessing the qualifications and skills necessary to migrate independently (Raghuram, 2008). In essence, the compounded effects of gender disparities and cultural norms have disproportionately affected Nepalese women within and beyond its borders, by continuing a cycle of unequal opportunities. However, recently, there has been an upswing trend of low-skilled Nepalese women, by seeking opportunities in the Indian labor market.

3. Motives for Migration

The decision for Nepalese women to migrate to India is often driven by a complex interplay of economic aspirations and socio-cultural factors. By seeking better employment opportunities, higher wages, and improved living conditions, many women view migration as a pathway to greater financial independence and empowerment in a region where traditional gender roles can curb their potential.

The data presented in Table 1 underscore the complex factors driving the migration of low-skilled Nepalese women to India. Across various border regions, the prime motive appears to be the perceived scarcity of employment opportunities in Nepal, with a substantial proportion of respondents, by showing this as a key factor. Notably, the data from Ilam, Pashupatinagar, Bhairahawa, Sunauli, and Biratnagar, Jogbani reveal that 94,1%, 100%, and 100% of respondents, respectively, identified the availability of job in India as one of the main reasons for their migration. Furthermore, many women expressed a desire for better employment prospects and an enhanced work status in India, by reflecting widespread dissatisfaction with their current employment conditions in Nepal.

As for the case of Jhapa, Kakarbhitta, the respondents displayed indifference when asked about their motives for migration. For these women, discussing their reasons seemed irrelevant, as they felt they had little choice in the matter. They did not see the point in explaining their motives, as, regardless of the reason, their primary aim was simply to migrate to India. In the context of Darchula, 84% of respondents emphasized the importance of improved work status in India as a driving factor for migration. Additionally, the data highlight the significance of being the primary income earner, with this factor varies in importance across different border regions. These findings illustrate the multifaceted nature of migration motives among Nepalese women, by encompassing economic necessity, aspirations for improved employment conditions, and broader socio-economic pressures they face within Nepal.

Table 1. Factors Motivating Nepalese Women´s Migration to India

|

Border |

Job opportunities in Nepal |

Feel of work status in India |

Sole earner |

|||

|

Yes |

No |

Satisfactory |

Not Satisfactory |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Ilam, Pashupatinagar |

5.9 |

94.1 |

94.1 |

5.9 |

41.2 |

58.8 |

|

Jhapa, Kakarbhitta |

93.3 |

6.7 |

NA |

NA |

26.7 |

73.3 |

|

Biratnagar, Jogbani |

66.7 |

33.3 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

|

Birgunj, Raxaul |

0 |

100 |

66.7 |

33.3 |

0 |

100 |

|

Janakpur, Bhittamore |

7.7 |

92.3 |

76.9 |

23.1 |

92.3 |

7.7 |

|

Bhairahawa, Sunauli |

100 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

100 |

|

|

Nepalgunj, Rupedia |

0 |

100 |

75 |

25 |

8.3 |

91.7 |

|

Dhangadi -Gauriphanta |

0 |

100 |

71.4 |

28.6 |

42.9 |

57.1 |

|

Kanchanpur -Gaddachauki |

66.7 |

33.3 |

66.7 |

33.3 |

66.7 |

33.3 |

|

Darchula, Dharchula |

4 |

96 |

84 |

16 |

8 |

92 |

Biratnagar, Jogbani and Birgunj, Raxaul highlight a strong link between dissatisfaction with Nepalese job opportunities and migration decisions. Janakpur, Bhittamore presents a mixed picture despite a low satisfaction rate (7,69%) with Nepalese job opportunities, a majority dissatisfaction rate (92,31%) migrates to India (Table 1), by showcasing the interplay of economic and possibly familial factors. Overall, economic considerations, particularly discontent with Nepalese job opportunities and the attraction of improved work status in India, emerge as primary motivators for migration. However, familial roles and social dynamics also contribute to shaping migration decisions, by indicating a nuanced interplay of factors across diverse regions.

Alongside this, there are several compelling factors motivating low-skilled Nepalese women to migrate to India. Firstly, the promise of better job opportunities acts as a significant driving force, as many perceive India as offering more employment prospects than their home country. Additionally, the desire to accompany their male counterparts, who may have already migrated for job opportunities or some other reasons, plays a crucial role in their decision-making process. Moreover, there is a notable social status associated with being employed, which serves as a motivator for these women. Employment not only provides them with financial independence, but also improves both their societal standing and sense of empowerment. Furthermore, the prospect of better educational opportunities for their children serves as a compelling factor for migration. Many of these women are driven by the desire to provide their children with access to quality education, which they believe India can offer more readily than Nepal. Overall, these motivating factors highlight the complex interplay of economic, social, and educational aspirations, which drive low-skilled Nepalese women to migrate to India in search of a better life for themselves and their families.

4. Status of Accommodation

The status of accommodation at the workplace plays a key role in shaping the migration experiences of Nepalese women in India. For many of them, the quality and security of housing directly influence their decision to migrate and remain employed. Inadequate or unsafe living conditions can lead to significant vulnerabilities, by including exploitation and health risks. On the other hand, decent accommodation can provide a sense of stability and safety, by making it easier for women to cope with the challenges of living and working away from home.

The data presented in Table 2 highlight the challenging living conditions faced by low-skilled Nepalese women in India, particularly concerning their accommodation. A striking observation is the overwhelming reliance on rented rooms, with a staggering 88,43% of respondents residing in such arrangements. This prevalence of rented accommodation underscores the limited options available to these women, many of whom are likely to be living in substandard and overcrowded conditions. Despite efforts by a small percentage (2,88%) who have managed to secure their own houses, the majority of them find themselves in precarious living situations, with a notable absence of ownership or stability in their housing arrangements. This underscores the urgent need for interventions aimed at improving the housing conditions of low-skilled migrant women in India, by ensuring their access to safe and adequate accommodation, which is conducive to their well-being and overall socio-economic stability.

|

Table 2. Status of Accommodation in India |

||||

|

Border |

Own house |

Rented Room |

Workplace |

Total |

|

Ilam, Pashupatinagar |

0 |

16.7 |

0 |

16.7 |

|

Jhapa, Kakarbhitta |

2.9 |

11.8 |

0 |

14.8 |

|

Biratnagar, Jogbani |

0 |

2.9 |

0 |

2.9 |

|

Birgunj, Raxaul |

0 |

2.9 |

0 |

2.9 |

|

Janakpur, Bhittamore |

0 |

11.8 |

0.9 |

12.7 |

|

Bhairahawa, Sunauli |

0 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

3.9 |

|

Nepalgunj, Rupedia |

0 |

7.8 |

3.9 |

11.8 |

|

Dhangadi, Gauriphanta |

0 |

6.9 |

0 |

6.9 |

|

Kanchanpur, Gaddachauki |

0 |

2.9 |

0 |

2.9 |

|

Darchula, Dharchula |

0 |

24.5 |

0 |

24.5 |

|

Total |

2.9 |

90.2 |

6.9 |

100 |

|

Percentage |

2.88 |

88.43 |

6.73 |

98 |

The survey data show that low-skilled Nepalese women migrating to India for work face significant challenges in securing suitable accommodation due to economic constraints and social barriers. The data reveal that only 2,9% of these women own their accommodation, while the majority of them struggle in substandard rented housing. With low wages from informal jobs, many of them cannot afford decent housing, often ending up in overcrowded or unsafe areas. Lack of legal documentation and unfamiliarity with urban environments also make it hard to secure rental agreements, by leaving them vulnerable to exploitation by landlords and employers. In some cases, they are forced to rely on intermediaries or brokers who may charge high fees or mislead them into poor living conditions. A similar kind of trend was discovered among the Mexican women in the USA (Fernández-Sánchez, 2020).

In addition to this, our data have revealed that cultural discrimination, particularly against foreign women, adds to their difficulties, with some landlords hesitant to rent to single women or migrants. Apart from this, many of them lack social support networks, by making it harder to find safe accommodations. Some women even fall victim to trafficking or abusive situations, especially if they migrate through unsafe channels. The housing shortage in Indian cities further exacerbates the issue, as competition for affordable housing is high, by pushing them into slums or temporary shelters with poor living conditions (Kumar, 2015). These factors create a cycle of insecurity, exploitation, and marginalization for Nepalese women in the Indian labor market.

While dealing with housing challenges, these women often find co-living or shared accommodation arrangements the sole alternative to meet their basic housing needs. By sharing rent and living space with other families, they reduce costs and gain companionship, which enhances safety and emotional support. These shared arrangements are particularly common among migrant communities, where women can rely on each other for assistance as for housing and work challenges (Aziz, 2015; Fernández-Sánchez, 2020). While co-living provides an immediate solution to housing struggles, finding trustworthy housemates can be a challenge. However, it offers a more sustainable and secure alternative to employer-provided housing or overcrowded informal settlements.

Such kind of accommodation and housing challenges are not unique among the Nepalese men migrants. However, for men, housing challenges are generally less critical because they face fewer social and safety risks compared to women. Men are less vulnerable to exploitation, harassment, or abuse, and often, they have more freedom to live in informal, low-cost accommodations without facing the same level of discrimination or isolation that women experience.

Our survey data reveal distinct residential patterns among low-skilled Nepalese women migrants across different border regions. Notably, in Darchula, 24,50% of these women migrate to India, yet none of them own homes there. This has been shaped by a complex interplay of socio-cultural, economic, and familial factors. Key issues include high illiteracy rates, poor economic conditions in their home regions, the pressure to send remittances regularly to support families back in Nepal, and the uncertainty of their future in India. These challenges significantly hinder their ability to afford suitable accommodation, by adding an extra layer of hardship to their migration experience. In addition, it is clear that high percentage of these women residing in rented rooms, similar to those in Ilam, reinforces the precarious nature of their living conditions. Thus, understanding the distribution of residential status among these migrant women is crucial for developing comprehensive support systems, which address not only their work-related challenges, but also the broader aspects of their everyday lives, by including housing, health, and familial structures.

5. Marital Status and Age Classifications of Migrant Women

Recent phenomena of married women’s migration, especially from the poor economic background, have demonstrated economic returns linked with their marital status (Bijwaard and van Doeselaar 2014). In the context of our study, the migration of low-skilled Nepalese women to India has also been shaped by a complex interplay of age, marital status, and familial responsibilities, each of which influences both the decision to migrate and the identification of underlying motives. Married women, typically in the age range of 25 to 40 years, often migrate out of necessity, driven by financial obligations, which stem from their roles as primary or supplementary income earners within their households. These women face considerable pressure to support their families in the context of scarce economic opportunities in Nepal, and migration becomes a strategic means to secure better employment prospects in India. Women’s decision to migrate is, therefore, largely motivated by the need to fulfil familial responsibilities, which include providing for children and managing household expenses (Singh, 1985). On the other hand, unmarried women, who are generally younger (between 18 and 25), have different migration goals. For them, migration is often tied to aspirations for financial independence and the desire to save money for future life events, such as marriage. These women are influenced by social expectations to contribute financially or improve their prospects before entering into marriage. Thus, our data have indicated that the migration patterns of low-skilled Nepalese women have been influenced by the diverse socio-economic realities that they face, with age and marital status playing pivotal roles in shaping both their decisions and motives.

Table 3. Marital Status and Age Classifications of Migrant Women

|

Marital Status |

Age Classification |

||||||

|

Regions |

Married |

Unmarried |

<20 |

20-29 |

30-39 |

40-48 |

>50 |

|

Ilam |

64.71 |

35.29 |

00 |

100 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

|

Jhapa |

66.67 |

33.33 |

26.67 |

73.33 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

|

Biratnagar |

100 |

00 |

00 |

100 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

|

Birgunj |

33.33 |

66.67 |

00 |

33.33 |

66.67 |

00 |

00 |

|

Janakpur |

100 |

00 |

00 |

100 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

|

Bhairahawa |

100 |

00 |

00 |

100 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

|

Nepalgunj |

100 |

00 |

00 |

25 |

33.33 |

25 |

16.67 |

|

Dhangadi |

85.71 |

14.29 |

00 |

42.86 |

28.57 |

28.57 |

00 |

|

Kanchanpur |

66.67 |

33.33 |

00 |

66.67 |

33.33 |

00 |

00 |

|

Darchula |

100 |

00 |

00 |

40 |

36 |

20 |

04 |

The data presented in Table 3 further illustrate the significant impact of marital status and age on migration patterns across various border regions of Nepal. In most regions, the majority of migrants were married women, as evidenced by regions, such as Biratnagar, Janakpur, and Bhairahawa, where 100% of the respondents were married women. This suggests that migration in these areas was predominantly driven by familial obligations and the need for married women to supplement household income. Conversely, Birgunj stands out with 66,67% of the respondents being unmarried, by indicating that migration in this region was influenced more by younger women’s desire for financial independence or savings for future marriage. From this perspective, age distribution across the regions highlights additional nuances. In regions like Ilam, Biratnagar, Janakpur, and Bhairahawa, women in the age range of 20-29 were dominant, by suggesting that early adulthood was a critical period for migration decisions. However, Jhapa reflected a younger demographic, with 26,67% of respondents being under 20, while Birgunj exhibited a broader age range, with a notable majority (66,67%) falling within the 30-39 age group. These regional variations suggest that while married women in their 20s make up the predominant migrant group in most areas. Local factors may also prompt migration among younger or older women, by demonstrating the multifaceted nature of the migration experience.

6. Indications of Job Satisfaction Status

The subsequent graph, which indicates the everyday livelihood outcomes of low-skilled Nepalese women in India, provides a nuanced understanding of their mental condition and satisfaction levels regarding various aspects of their migration journey. Notably, the subsequent graph reveals significant regional variations in the satisfaction levels of women across 10 different borders. Women from Ilam, Pashupatinagar, Janakpur, Bhittamore exhibit higher satisfaction compared to their counterparts from Biratnagar, Jogbani, Kanchanpur, Gaddaachauki, and Birgunj, Raxaul.

This disparity suggests that the experience of migration and job satisfaction is influenced by regional factors, potentially including economic opportunities, social support networks, and overall living conditions. To explain it further, women from economically prosperous bordering regions experience higher job satisfaction, largely due to their access to better economic opportunities, strong social support networks, and improved living conditions. In particular, those coming from the eastern regions of Nepal exhibit a greater familiarity with migration patterns and face less pressure to send remittances, which contributes to their overall well-being. This familiarity, combined with relatively favorable economic conditions, enhances their integration outcomes and positively impacts their job satisfaction levels.

Although these women migrated to India to escape limited opportunities in Nepal, they remained dissatisfied with their working and living conditions. They faced low wages and struggled to allocate funds for future needs. Despite their frustrations, they felt forced to stay in India in the absence of more favorable alternatives in Nepal. This highlights the tough reality faced by many low-skilled Nepalese migrants trying to improve their economic income.

One striking observation is the situation of women from Darchula, Dharchula where, despite being the highest in number with 25 migrants, every single woman expressed dissatisfaction with their entire migration journey, work, life, and settlement (Figure 1). This finding unveils a complex and vicious scenario, by highlighting the desperation, which may make these women to migrate from Nepal. The dissatisfaction despite the large-scale migration underscores the severity of challenges faced, by indicating a pressing need for interventions, which address the root causes of dissatisfaction, potentially related to limited economic opportunities, exploitative working conditions, and the lack of support structures. The graph further underscores the intersectionality of various factors, such as family background, education, language, skills, and age, by emphasizing the need for a holistic approach to understanding and addressing the mental well-being of these low-skilled Nepalese women in India.

Furthermore, based on the interview data, we can argue that deeply entrenched patriarchal norms in both the Nepalese and Indian contexts further curtail women’s empowerment. Male-dominated labor market sectors direct women into informal household jobs, while barriers to skills development hinder their career path and growth. Those migrating women with children lack childcare options, by forcing them to balance their main source of income with all domestic duties and child-rearing. Poor housing in slum areas compounds difficulties. Additionally, the social stigma associated with low-status work, which is considered shameful, along with health risks from hazardous labor without healthcare access over time, give a comprehensive view of adversity, by confronting Nepalese women undertaking precarious informal employment in India. Despite the proximity, low-skilled irregular migration pathways continue to face intersectional challenges. To conclude, we can argue that an interplay of limited social capital, financial deprivation, lack of legal protections, social norms, hazardous work, and irregular status converge to define the potential benefits of migration to India for Nepalese women in low-wage roles.

7. Outcome Synthesis

The survey data have revealed that many Nepalese women have found migration to India a better alternative for their overall enhancement than living in Nepal. Many women perceived migration to India, as a promising avenue for personal and familial progress. They believed that this migration has helped them to foster better livelihoods and increased living standards and quality of life in various aspects.

While low-skilled Nepalese women undertaking manual work in India face immense hardships, their migration has also produced some socioeconomic benefits and personal advancement. Based on our data, what we can claim is that, on the financial front, these women often became the sole earners for households back in Nepal. It is evident that remittance sent by the emigrated population has supported family sustenance, children’s education, healthcare, and debt repayment (Bhadra, 2007; Eurostat et al., 2016; Ratha et al., 2016). With few local opportunities, their income from India underpinned entire families’ survival. Some women have managed to purchase land or housing in Nepalese cities from their earnings, by allowing upward socioeconomic status. Despite minimal wages and savings potential in India, their persistent labour provided basic financial security for households depending on their contributions.

Beyond finances, migration also enabled some women to overcome gendered constraints and exercise greater autonomy in personal domains. Moving abroad alone allowed them to escape from oppressive marital, family or traditional structures (Bhadra, 2007; Kofman et al., 2005; Maslak, 2003). The absence of male relatives’ control permits increased agency in decision-making over finances, mobility, and healthcare. Working abroad fostered self-reliance and confidence (Kofman et al., 2005). Apart from this, our data showcased that some Nepalese women utilized migration to delay or avoid unwanted marriages or gain skill training for future enterprises.

In brief, while migration to India remains an uphill battle, it does allow marginalized Nepalese women to support households, enhance social capital, and avoid certain patriarchal barriers through economic participation - even if limited in scope. Despite saying so, the trends of borders were found to have been varied. While comparing this trend, our data demonstrated the following scenario:

Bottom of Form

Our study reveals that low-skilled Nepalese women perceive migration as both an opportunity and a challenge, by indicating a nuanced perspective on the transformative effects of their migration to India. While they acknowledge the potential for socio-economic empowerment through migration, they also recognize the inherent difficulties and hindrances they face in this process. Nevertheless, a predominant theme, which emerged from our findings is the linkage between migration and the lack of opportunities in Nepal. Many of these women conceive migration as a necessity driven by the dearth of viable prospects within their home country, by highlighting the complex interplay between push and pull factors, by shaping their migration decisions.

Despite the challenges associated with low-skilled work in India, our research underscores the significant transformative changes, which migration has brought about in Nepalese women’s lives. By breaking free from traditional gender roles prevalent in Nepal, these women engage in diverse low-skilled jobs in India, by leading to newfound economic independence and empowerment. This economic autonomy not only enhances their personal agency, but also yields positive ripple effects on their families back in Nepal. The income earned from migration serves as a lifeline, by enabling crucial investments in education, healthcare, and basic needs, thereby improving their families’ overall well-being.

Moreover, our study highlights the tangible long-term economic impact of migration on low-skilled Nepalese women and their families. Beyond immediate consumption needs, some women have been able to save and invest in assets, such as land and real estate in Nepal. This strategic allocation of resources not only enhances their financial security, but also contributes to the socio-economic development of their communities. Thus, our findings emphasize the multi-dimensional benefits of migration for low-skilled Nepalese women, by illustrating its potential to catalyze positive change and foster long-term prosperity for both individuals and their families.

However, it is imperative to recognize the nuanced nature of migration. While these positive aspects are evident, challenges related to working conditions, social integration, and legal protections cannot be overlooked. Migration also poses complexities for families left behind and may strain personal relationships (Bhadra, 2007; Duda-Mikulin, 2013). A holistic understanding of migration encompasses both its empowering aspects and the need for comprehensive support structures in order to address the multifaceted impacts on both individuals and communities.

8. Recommendations

In light of the findings resulting from our survey report, several key recommendations emerge to address the challenges and capitalize on the opportunities presented by the migration of low-skilled Nepalese women to India. Firstly, there is a pressing need for concerted efforts to address economic disparities within Nepal. This entails implementing targeted interventions, such as skills development programs and fostering small-scale enterprises, particularly in marginalized communities, in order to create sustainable employment opportunities. By enhancing economic prospects domestically, Nepal can reduce the necessity for migration and empower women to make autonomous decisions regarding their livelihoods. Simultaneously, initiatives aimed at promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment should be prioritized in both Nepal and India. These efforts should encompass equal access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities for women, alongside measures to fight gender-based discrimination and violence. Additionally, social protection measures need strengthening to ensure the well-being and safety of migrant women, by including access to affordable housing, healthcare, and legal assistance, both in the host country and India, for families left behind.

In order to enhance the socio-economic development and empowerment of Nepalese women migrating to India, several key recommendations should be prioritized. First, promoting financial inclusion and savings initiatives among migrant women is essential to achieving financial autonomy and independence. Facilitating their access to formal banking services, developing targeted financial literacy programs, and supporting the creation of community-based savings and credit groups can empower these women to manage and invest their earnings more effectively. This will ultimately improve their long-term financial security and resilience.

In addition, fostering collaboration and knowledge-sharing among key stakeholders involved in migration governance is crucial. The Government of Nepal should work closely with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), migrant advocacy groups, and international agencies, such as the International Labor Organization (ILO) and UN Women. By engaging in structured dialogues, these stakeholders can develop coordinated policies, which address the specific challenges faced by low-skilled Nepalese women migrating to India, by including issues of labor rights, exploitation, and access to social protections.

Moreover, local governments, civil society organizations, and academic institutions in both Nepal and India should collaborate in order to implement sustainable programs that focus on skills development, safe migration practices, and reintegration support. Through such partnerships, stakeholders can harness the full potential of migration in order to promote gender equality and socio-economic growth.

9. Conclusion

Many scholars have highlighted the transformative potential of women’s migration to prosperous nations, particularly regarding their access to economic opportunities and overall development (Aziz, 2015; Ballarino and Panichella, 2017; Duda Mikulin, 2013; Mishra, 2022). To some extent, this context seemed to be true in the case of Nepalese women who have chosen to migrate to various developed countries like Australia, Canada, the USA, Japan, and the UK (Bohra-Mishra, 2011; Malla and Shrestha, 2000; Mishra, 2022). However, especially the low-skill women migrating to India for manual work face substantial hardships rooted in multiple factors. Firstly, their limited social capital and irregular migrant status heighten vulnerability. Most women have weak social networks in India and do not speak Hindi, by hampering access to job information, rights awareness, and support systems. Irregular migration without proper documents also restricts their access to basic state protections and benefits. Financial pressures are immense with no family support, while exploitative working conditions like wage theft, abuse, and excessive hours are commonplace due to a lack of regulatory control.

The demographic data presented here provides valuable insights into the everyday livelihood status of low-skilled Nepalese women who have migrated to India. The majority of these women, comprising a staggering 90,20% of the total, particularly those from Darchula, Dharchula, predominantly reside in rented accommodation. However, a nominal percentage of women from Jhapa, Kakarbhitta, seemed to possess their own houses in India. From our survey, we can argue that the absence of ownership of houses suggests a lack of permanent settlement, by indicating that these women are likely engaged in temporary and precarious working arrangements. The concentration in rented accommodations also underscores the transient nature of their employment, which may contribute to their vulnerability. Reliance on rented rooms can lead to instability and insecurity due to the temporary nature of such arrangements, as individuals, they may face frequent relocations and financial pressure from fluctuating rental prices. Additionally, limited control over their living environment and the threat of eviction can create a constant sense of uncertainty, by impacting overall well-being. Thus, these highlights the need for targeted interventions to address issues related to housing and social support.

10. References

Aziz, Karima. (2015). “Female Migrants” Work Trajectories: Polish Women in the UK Labour Market’. Central and Eastern European Migration Review, 4(2),87-105.

Ballarino, Gabriele & Nazareno, Panichella. (2017). The Occupational Integration of Migrant Women in Western European Labour Markets Internal Migration in Italy View Project DESO: Direct Effect of Social Origin on Socio-Economic Outcomes View Project. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699317723441

Bhadra, Chandra. (2007). International Labour Migration of Nepalese Women: The Impact of their Remittances on Poverty Reduction. The Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade (ARTNeT) Aims at Building Regional Trade Policy and Facilitation Research Capacity in Developing. Vol. 44.

Bijwaard, Govert E. & Stijn van Doeselaar. (2014). The Impact of Changes in the Marital Status on Return Migration of Family Migrants. Journal of Population Economics, 27(4), 961-97. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-013-0495-3

Bohra-Mishra, Pratikshya. (2011). Nepalese Migrants in the United States of America: Perspectives on Their Exodus, Assimilation Pattern and Commitment to Nepal. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(9), 1527-37. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.623626

Duda-Mikulin, Ewa. (2013). Migration as Opportunity? A Case Study of Polish Women: Migrants in the UK and Returnees in Poland. Problemy Polityki Spo\lecznej. Studia i Dyskusje, 23(4), 105-21.

Eurostat, Further, Robert Obrzut This, European Union, and Eurostat Figure. (2016). Personal Remittances Statistics. (February 2015), 1-11.

Farris, S. R. (2015). Migrants’ Regular Army of Labour: Gender Dimensions of the Impact of the Global Economic Crisis on Migrant Labor in Western Europe. The Sociological Review, 63(1), 121-143. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12185

Fernández-Sánchez, Higinio. (2020). Transnational Migration and Mexican Women Who Remain behind: An Intersectional Approach. PLOS ONE, 15(9), e0238525. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238525

Kofman, Eleonore. (2005). Gendered Migrations, Livelihoods and Entitlements in European Welfare Regimes.

Kofman, Eleonore; Phizacklea, Annie; Raghuram, Parvati & Sales, Rosemary. (2005). Gender and International Migration in Europe: Employment, Welfare and Politics. Psychology Press.

Kofman, Eleonore & Raghuram, Parvati. (2006). Gender and Global Labour Migrations: Incorporating Skilled Workers. Antipode, 38(2), 282-303. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2006.00580.x

Kumar, Arjun. (2015). Housing Shortages in Urban India and Socio-Economic Facets. Journal of Infrastructure Development, 7(1), 19-34. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0974930615578499

Malla, Sapana Pradhan, and Shrestha, Bidhya Laxmi. (2000). Baseline Study on Inheritance Right of Women. Forum for Women, Law and Development.

Maslak, Mary Ann. (2003). Daughters of the Tharu: Gender, Ethnicity, Religion, and the Education of Nepali Girls. Routledge.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Nepal. (2020). Nepal Labour Migration Report.

Mishra, Manamaya. (2022). Female Labour Migration: Gender Prospective.

Purkayastha, Bandana. (2005). Skilled Migration and Cumulative Disadvantage: The Case of Highly Qualified Asian Indian Immigrant Women in the US. Geoforum, 36(2), 181-96. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2003.11.006

Raghuram, Parvati. (2008). Migrant Women in Male-Dominated Sectors of the Labour Market: A Research Agenda. Population, Space and Place, 14(1), 43-57. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.472

Ratha, Dilip; De, Supriyo; Plaza, Sonia; Schuettler, Kirsten; Shaw, William; Wyss, Hanspeter & Yi, Soonhwa. (2016). Migration and Development Brief April 2016: Migrati.

Rukamanee Maharjan. (2023). Nepalese Girls Still Don’t Have Equal Educational Opportunities.

Singh, J. P. (1985). Marital Status and Migration in Bihar, West Bengal and Kerala: A Comparative Analysis. Sociological Bulletin, 34(1-2), 69-87. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0038022919850104

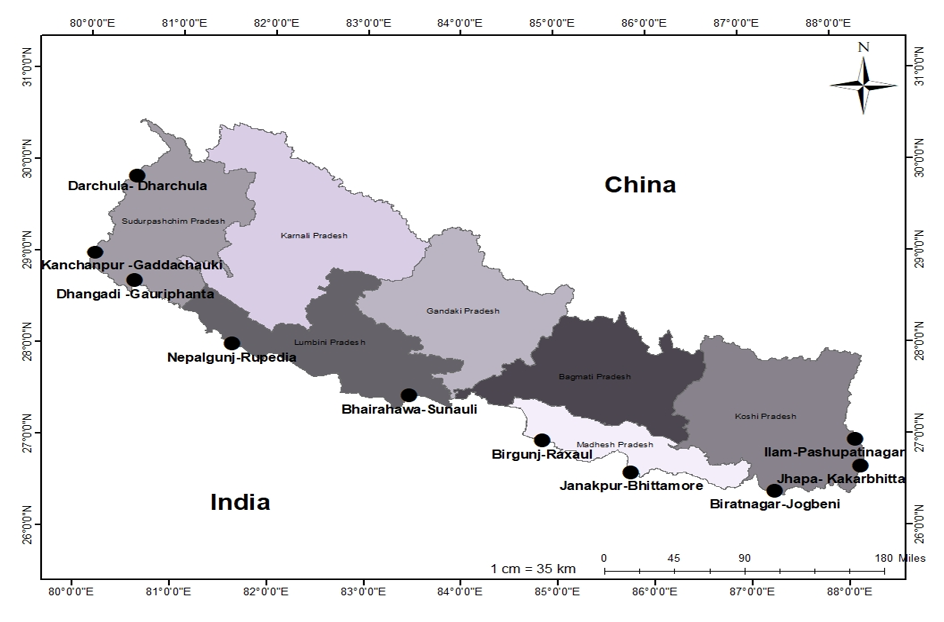

ANNEX 1:

Location of study sites (Total 10) in the border between Nepal and India

Source: Field Data

Source: Field Data

Source: Field Data

Figure 1. Job Satisfaction of Migrant Nepalese Women in India

Source: Field Data

Map source: Department of Survey, Nepal; Modified with study borders.